Actions: The Principle of Cause and Effect

From Words of My Perfect Teacher:

Chapter 4

Actions: The Principle of Cause and Effect*

(*The Sanskrit word karma, now often used in English to denote the result of past actions, in fact simply means “action.”)

You renounce evil and take up good, as in the teachings on cause and effect.

Your action follows the progression of the Vehicles.*

Through your perfect view you are free from all clinging.

Peerless Teacher, at your feet I bow.

(*Following the progression of the vehicles (Skt. yana) means that externally one follows the discipline of the Sravakayana while internally one practises the Mahayana, and secretly one practises the Mantrayana. Here Patrul Rinpoche means that his teacher, although his mind is wholly beyond samsara, is nonetheless a perfect example to his disciples of how to follow the progressive path.)

The way this chapter should be explained and studied is with the same attitude as for the others. The subject is explained under three headings: negative actions, which should be abandoned; positive actions, which should be adopted; and the all-determining quality of actions.

I. NEGATIVE ACTIONS TO BE ABANDONED

What causes us to be reborn in the higher or lower realms of samsara is the good and bad actions that we ourselves have accumulated. Samsara itself is produced by actions, and consists entirely of the effects of actions-there is nothing else that consigns us to the higher or lower realms. Neither is it just chance. At all times, therefore, we should examine the effects of positive and negative actions, and try to avoid all

those that are wrong and take up those that are right.

1. The ten negative actions to be avoided

Three of these ten are physical acts: taking life, taking what is not given, and sexual misconduct; four are verbal acts: lying, sowing discord, harsh words, and worthless chatter; and three are mental acts: covetousness, wishing harm on others, and wrong views.

1.1 TAKING LIFE

Taking life means doing anything intentionally to end the life of another being, whether human, animal or any other living creature.

A warrior killing an enemy in battle is an example of killing out of hatred. Killing a wild animal to eat its flesh or wear its skin is killing out of desire. Killing without knowing the consequences of right and wrong or, like certain tirthikas, in the belief that it is a virtuous thing to do – is killing out of ignorance.

There are three instances of killing that are called acts with immediate retribution, because they bring about immediate rebirth in the hell of Ultimate Torment without passing through the intermediate state: killing one’s father, killing one’s mother and killing an Arhat.*

(*The two other acts with immediate retribution are to cause a schism within the Sangha and to shed the blood of a Buddha.)

Some of us, thinking only of the specific act of killing with our own hands, might imagine that we are innocent of ever having taken life. But to start with, there is no one, high or low, powerful or feeble, who is not guilty of having crushed countless tiny insects underfoot while walking around.

More specifically, lamas and monks visiting their benefactors’ houses are served the flesh and blood of animals that have been slaughtered and cooked for them, and such is their predilection for the taste of meat that without the least remorse or compassion for the slaughtered beasts they wolf it all down with great gusto. In such cases, the negative karmic effect of the slaughter falls on both benefactor and guest without distinction.

When important people and government officials travel about, wherever they go, innumerable animals are killed for their tea-parties and receptions. The rich as a rule kill countless animals. Of all their livestock, apart from the odd beast here and there, they allow none to die a natural death but have them slaughtered one by one as they age. What is more, in summer these very cattle and sheep, as they graze, kill innumerable insects, flies, ants and even little fish and frogs, swallowed down with the grass, crushed under their hooves or swamped in their dung. The negative karmic result of all these acts comes to the owner as well as the beast. Compared to horses, cattle and other livestock, sheep are a particularly prolific source of harm. As they graze they eat all sorts of little animals frogs, snakes, baby birds, and so on. In summer at shearing time, hundreds of thousands of insects carried by each sheep in its fleece all die. In winter at lambing time, no more than half the lambs are kept; the rest are killed at birth. The mother ewes are used for their milk and to produce lambs until they become too old and exhausted, at which point they are then all slaughtered for their meat and skins. And not a single ram, whether castrated or not, reaches maturity without being slaughtered straight away. Should the sheep have lice, millions of them are killed at a time on each sheep. Anyone who owns a flock of a hundred or more sheep can be sure of at least one rebirth in hell.

For every marriage, innumerable sheep are slaughtered when the dowry is sent, when the bride is seen off, and when she is received by her in-laws. Afterwards, every time the young bride goes back to visit her own family, another animal is sure to be killed. Should her friends and relatives invite her out and serve her anything but meat, she affects a shocked loss of appetite and eats with a pretentious disdain as if she had forgotten how to chew.* But kill a fat sheep and set down a big pile of breast-meat and tripe before her, and the red-faced little monster sits down seriously, pulls out her little knife, and gobbles it all down with much smacking of lips. The next day she sets off loaded down with the bloody carcass, like a hunter returning home but worse, for every time she goes out she is sure not to come back empty-handed.

(*In most of Tibetan society of the time, eating meat at every meal would have been considered a sign of wealth and therefore of high status. The guest is acting pretentiously in trying to give the impression that she is unaccustomed to eating anything but meat in her own home.)

Children, too, cause the death of countless animals while they are playing, whether they are aware of it or not. In summer, for instance, they kill many insects just by beating the ground with a willow-wand or leather whip as they walk along.

So all of us humans, in fact, spend our entire time taking life, like ogres. Indeed-considering how we slaughter our cattle to enjoy their flesh and blood when they have spent their whole lives serving us and feeding us with their milk as if they were our mothers-we are worse than any ogre.

The act of taking life is complete when it includes all four elements of a negative action. Take the example of a hunter killing a wild animal. First of all, he sees an actual stag, or musk-deer, or whatever it might be, and identifies the animal beyond any doubt: his knowing that it is a living creature is the basis for the act. Next, the wish to kill it arises: the idea of killing it is the intention to carry out the act. Then he shoots the animal in a vital point with a gun, bow and arrow or any other weapon: the physical action of killing is the execution of the act. Thereupon the animal’s vital functions cease and the conjunction of its body and mind is sundered: that is the final completion of the act of taking a life.

Another example: the slaughter of a sheep raised for meat by its owner. First, the master of the house tells his servant or a butcher to slaughter a sheep. The basis is that he knows that there is a sentient creature involved-a sheep. The intention, the idea of killing it, is present as soon as he decides to have this or that sheep slaughtered. The execution of the actual act of killing takes place when the slaughterer seizes his noose and suddenly catches the sheep that he is going to kill, throws it on its back, lashes its legs together with leather thongs and binds a rope around its muzzle until it suffocates. In the violent agony of death, the animal ceases to breathe and its staring eyes turn bluish and cloud over, streaming tears. Its body is dragged off to the house and the final phase, the ending of its life, reaches completion. In no time at all the animal is being skinned with a knife, its flesh still quivering because the “all-pervading energy”* has not yet had time to leave the body; it is as if the animal were still alive. Immediately it is roasted over a fire or cooked on the stove, and then eaten. When you think about it, such animals are practically eaten alive, and we humans are no different from beasts of prey.

(*One of the five subtle energies (rlung), or “winds,” in the body.)

Suppose that you intended to kill an animal today, or that you said you would, but did not actually do so. There would already be the basis, the knowledge that there is a sentient being, and the intention, the idea of killing it. Two of the elements of the negative action would therefore have been fulfilled, and although the harm would be less heavy than if you had in fact completed the act of killing, the stain of a negative act, like a reflection appearing in a mirror, would nevertheless remain.

Some people imagine that only the person who physically carries out the killing is creating a negative karmic effect, and that the person who just gave the orders is not – or, if he is, then only a little. But you should know that the same karmic result comes to everyone involved, even anyone who just felt pleased about it – so there can be no question about the person who actually ordered that the killing be carried out. Each person gets the whole karmic result of killing one animal. It is not as if one act of killing could be divided up among many people.

1.2 TAKING WHAT IS NOT GIVEN

Taking what is not given is of three kinds: taking by force, taking by stealth and taking by trickery.

Taking by force. Also called taking by overpowering, this means the forceful seizure of possessions or property by a powerful individual such as a king having no legal right to them. It also includes plunder by force of numbers, as by an army, for example.

Taking by stealth. This means to take possession of things secretly, like a burglar, without being seen by the owner.

Taking by trickery. This is to take others’ goods, in a business deal for example, by lying to the other party, using false weights and measures or other such subterfuges.

Nowadays, the idea that in business or in other contexts there is anything wrong with cheating or trickery to get things from others does not occur to us, as long as we are not overtly stealing. But in fact any profit we may make by deceiving other people is no different from outright theft.

In particular, lamas and monks these days see no harm or wrong in doing business; indeed they spend their whole lives at it, and feel rather proud of their prowess. However, nothing debilitates a lama or monk’s mind more than business. Engrossed in his transactions, he feels little inclination to pursue his studies or to work at purifying his obscurations and anyway there is no time left for such things. All his waking hours until he lies down to sleep at night are spent poring over his accounts. Any idea of devotion, renunciation or compassion is eradicated and constant delusion overpowers him.

Jetsun Milarepa arrived one night at a monastery and lay down to sleep in front of the door of a cell. The monk who lived in the cell was lying in bed thinking about how he was going to sell the carcass of a cow that he planned to have slaughtered the next day: “I’ll get that much for the head … the shoulder-blade is worth that much, and the shoulder itself that much… that much for the knuckles and shins…” He went on calculating the value of each and every part of the cow, inside and out. By daybreak, he had not slept a wink but he had it all worked out except the price he would ask for the tail. He got up straight away, completed his devotions and made torma-offerings.

As he stepped outside he came across the Jetsun still sleeping, and disdainfully railed at him, “You claim to be a Dharma-practitioner, and here you are still sleeping at this hour! Don’t you do any practice or recitation at all?”

“I don’t always sleep like this,” replied Jetsun Mila. “It’s just that I spent the whole night thinking about how to sell a cow of mine that’s going to be slaughtered. I only got to sleep a little while ago…” And so, exposing the monk’s hidden shortcomings, he left.

Like the monk in this story, those whose lives at the moment are devoted only to business spend day and night totally involved in their calculations. They are so engrossed in delusion that, even when death comes, they will die still as deluded as ever. Moreover, commerce involves all sorts of negative actions. People who have merchandise to sell, however shoddy in reality, extol its qualities in whatever ways they can think up. They tell outright lies, such as how this or that potential buyer has already offered this much for it, which they had refused; or how they originally bought it for this or that huge sum. Trying to buy something that is already the subject of negotiations between two other people, they resort to slander to provoke disagreement between the two parties. They use harsh words to insult their competitors’ wares, to extort debts and the like. They indulge in worthless chatter by demanding ridiculous prices or haggling for things that they have no intention of buying. They envy and covet other people’s possessions, trying their best to be given them. They wish harm on their competitors, wanting always to get the better of them. If they trade in livestock, they are involved in killing. So business, in fact, involves all of the ten negative actions except perhaps wrong views and sexual misconduct. Then, when their deals go wrong, both sides have wasted their assets, everyone suffers, and traders may end up starving, having brought harm upon both themselves and their counterparts. But should they have some success, however much they make it is never enough. Even those who get as rich as Vaisravana still take pleasure in their nefarious business deals. As death finally closes in on them they will beat their breasts in anguish, for their entire human life has been spent in such obsessions, which now become millstones to drag them down to the lower realms.

Nothing could be more effective than trade and commerce for piling up endless harmful actions and thoroughly corrupting you. You find yourself continually thinking up ways to cheat people as though you were looking through a collection of knives, awls and needles for the sharpest tool. Brooding endlessly over harmful thoughts, you turn your back on the bodhicitta ideal of helping others, and your pernicious acts multiply to infinity.

Taking what is not given also has to include the four elements already explained for the negative action to be complete. However, any participation, down to merely offering hunters or thieves some food for their expedition, is enough to bring you an equal share of the effect of the evil action of their killing or stealing.

1.3 SEXUAL MISCONDUCT

The rules that follow are for laypeople. In Tibet, during the reign of the Dharma King Songtsen Gampo, laws based on the ten positive actions were established comprising both rules for the laity and rules for the religious community. Here, we are referring to those restrictions on behaviour destined for laypeople, who, as householders, should follow an appropriate ethic. Monks and nuns, for their part, are expected to avoid the sexual act altogether.

The gravest sexual misconduct is that of leading other people to break their vows. Sexual misconduct also includes acts associated with particular persons, places and circumstances: masturbation; sexual relations with a person who is married, or committed to someone else; or with a person who is free, but in broad daylight, during observation of a one-day vow, during illness, distress, pregnancy, bereavement, menstruation, or recovery from child-birth; in a place where the physical representations of the Three Jewels are present; with one’s parents, other prohibited family members, or with a prepubescent child; in the mouth or anus, and so on.

1.4 LYING

Lying is of three sorts: ordinary lies, major lies and phoney lama’s lies.

Ordinary lies. These are any untrue statements, made with the intention of deceiving other people.

Major lies. These are statements such as, for example, that there is no benefit in positive actions and no harm in negative ones, that there is no happiness in the Buddhafields and no suffering in the lower realms, or that the Buddhas have no good qualities. They are called major lies because no other lies could have more devastatingly misleading consequences.

Phoney lama’s lies. These are all untrue claims to possess such qualities and abilities as, for example, to have attained the Bodhisattva levels, or to have powers of clairvoyance. Imposters nowadays have more success than true masters, and everyone’s thoughts and actions are easy to influence. So some people declare themselves masters or siddhas in an effort to deceive others. They have had a vision of a certain deity and made thanksgiving offerings to him, they claim, or they have seen a spirit and chastised it. For the most part these are just phoney lama’s lies, so be careful not to believe such cheats and charlatans blindly. Affecting as it does both this life and the next, it is important to place your trust in a Dharma practitioner whom you know well, who is humble and whose inner nature and outer behaviour correspond.

Generally speaking, there are ordinary people who have some degree of concept-bound clairvoyance, but it is intermittent, and only valid some of the time. Pure clairvoyance comes only to those who have reached the sublime levels, and is therefore extremely hard to attain.*

(*Here Patrul Rinpoche distinguishes between psychic phenomena unrelated to wisdom and the real transcendence of space and time of realized beings, who have attained the three highest Bodhisattva levels. The former are described as being “tainted” (by concepts), and the latter as untainted.)

1.5 SOWING DISCORD

Sowing discord can be either open or secret.

Openly sowing discord. This is a strategy often used by people who hold some authority. It consists of creating a rift between two people both present by openly telling one that the other said something bad about him behind his back, and going on to describe what the first person said or did to harm the second-and then perhaps asking them both why today they are still behaving as if no such thing had happened between them.

Secretly sowing discord. This means to separate two people who get on well by going to see one of them, behind the other’s back, to report what terrible things the second, whom the first cares for so much, has supposedly been saying about him or her.

The worst instance of sowing discord is to cause conflict between members of the Sangha. It is particularly serious to cause a rift between a teacher of the Secret Mantrayana and his disciples, or among the circle of spiritual brothers and sisters.

1.6 HARSH SPEECH

Harsh speech is, for instance, to make rude remarks about other people’s unsightly physical flaws, openly calling them one-eyed, deaf, blind, and so on. It includes revealing others’ hidden shortcomings, offensive talk of all kinds and, in fact, any words that make other people unhappy or uncomfortable, even if spoken sweetly rather than harshly.

In particular, to speak offensively in front of one’s teacher, a spiritual friend or a holy being is a very grave error.

1.7 WORTHLESS CHATTER

Worthless chatter means talking a lot without any purpose: for example, reciting what one imagines to be Dharma but is not – such as the rites of brahmins;* or talking aimlessly about subjects that stir up attachment and hatred, like telling tales of prostitutes, singing libidinous songs, or discussing robbery and war. In particular, to disturb people’s prayers or recitation by distracting them with a flood of useless words is especially harmful, since it prevents them from accumulating merit.

(*”The rites of brahmins” refers to rites performed without the motivation of attaining enlightenment for all beings. Although they are religious rituals they are not considered to lead to ultimate liberation.)

Pieces of gossip that seem to have come up quite naturally and spontaneously are for the most part, when you look more closely, motivated by desire or hatred, and the gravity of the fault will be in proportion to the amount of attachment or hatred created in your own or others’ minds.

While you are saying prayers or reciting mantras, mixing them with irrelevant talk will stop them bearing any fruit, no matter how many you say. This applies especially to the different kinds of gossip that circulate along the rows of the gathered Sangha. One single gossip-monger can cause the merit of a whole congregation to be spoiled and the meritorious actions of its benefactors and patrons to be wasted.

In the noble land of India, as a rule, only those who had the highest attainments and were free from all harmful defects had the right to use funds donated to the Sangha, and the Buddha permitted no-one else to do so. But nowadays people learn one or two tantric rituals and, as soon as they can recite them, they start to use whatever dangerous offerings* they can get. Without having received the empowerments, without having maintained all the samayas, without having mastered the generation and perfection phases and without having completed the requirements of the mantra recitation, to obtain offerings by performing tantric rituals – just chanting the secret mantras perfunctorily like bonpo sorcerers – is a serious transgression. To use these dangerous donations is comparable to eating pills of burning iron: if ordinary people partake of them without having the cast-iron jaws of the union of the generation and perfection phases, they will burn themselves up and be destroyed.

(*Because of the very sacredness of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, the misuse of offerings made to them has especially heavy karmic consequences. Here particular reference is made to the offerings of the faithful for rituals performed for the dead, the sick, etc.)

As it is said:

Dangerous offerings are lethally sharp razors:

Consume them and they’ll cut the life-artery of liberation.

Far from having any mastery of the two phases of the meditation, such people, who may at least know the words of the ritual, do not even bother to recite those properly. Worse still, the moment they get to the mantra recitation – the most important part – they start chatting, and let loose an endless stream of irrelevant gossip full of desire and aggression for the whole of the allocated time. This is disastrous for themselves and others. It is most important that monks and lamas should give up this kind of chatter and concentrate on reciting their mantras without talking.

1.8 COVETOUSNESS

Covetousness includes all the desirous or acquisitive thoughts, even the slightest ones, we might have about other people’s property. Contemplating how agreeable it would be if those wonderful belongings of theirs were ours, we imagine possessing them over and over again, invent schemes to get hold of them, and so on.

1.9 WISHING HARM ON OTHERS

This refers to all the malicious thoughts we might have about other people. For example, brooding with hatred or anger about how we might harm them; feeling disappointed when they prosper or succeed; wishing they were less comfortable, less happy or less talented; or feeling glad when unpleasant things happen to them.

1.10 WRONG VIEWS

Wrong views include the view that actions cause no karmic effect, and the views of eternalism and nihilism.

According to the view that actions cause no karmic effect, positive actions bring no benefit and negative actions no harm. The views of eternalism and nihilism include all the different views of the tirthikas, which, although they can be divided into three hundred and sixty false views or sixty-two wrong views, can be summed up into the two categories of eternalism and nihilism.

Eternalists believe in a permanent self and an eternally existing creator of the universe, such as Isvara or Visnu. Nihilists believe that all things just arise by themselves and that there are no past and future lives, no karma, no liberation and no freedom.

As it says in the doctrine of Black Isvara:

The rising of the sun, the downhill flow of water,

The roundness of peas, the bristling length and sharpness of thorns,

The beauty of the iridescent eyes of peacocks’ tails:

No-one created them, they all just naturally came to be.

They argue that when the sun rises in the east, no-one is there to make it rise. When a river flows downhill, nobody is driving it downwards. No-one rolled out peas to make them all so round, or sharpened all the long and bristling points of thorns. The beautiful multicoloured eyes on a peacock’s tail were not painted by anyone. All these things just are so by their own nature, and so it is with everything in this world whether pleasant or unpleasant, good or bad-all phenomena just arise spontaneously. There is no past karma, there are no previous lives, no future lives.*

(*This view is considered incorrect not because it denies a creator, but because it denies the process of causality.)

To consider the texts of such doctrines true and to follow them, or even without doing so, to think that the Buddha’s words, your teacher’s instructions or the texts of the learned commentators are in error and to doubt and criticize them, are all included in what is meant by wrong views.*

(*This does not mean that one should not question or analyse the teachings. Indeed, the Buddha encouraged such questioning. However, allowing one’s opinions to close one’s mind to the Buddhist teachings, which often challenge everyday concepts, can actually prevent one from adopting the path that leads to freedom.)

The worst of the ten negative actions are taking life and wrong views.

As it is said:

There is no worse action than taking another’s life;

Of the ten unvirtuous acts, wrong view is the heaviest.

Except for those in the hells, there is no being who does not shrink from death or who does not value his or her life over anything else. So to destroy a life is a particularly negative action. In the Sutra of Sublime Dharma of Clear Recollection, it is said that one will repay any life one takes with five hundred of one’s own lives, and that for killing a single being one will spend one intermediate kalpa in the hells.

Even worse is to take some meritorious work you may be involved in, such as building a representation of the Three Jewels, as an excuse for committing harmful actions such as killing. Padampa Sangye says:

To build a support for the Three Jewels while causing harm and suffering

Is to cast your next life to the wind.

It is equally wrong, mistakenly thinking you are doing something meritorious, to slaughter animals and offer their flesh and blood to lamas invited to your house or to an assembly of monks. The negative karmic effect of the killing comes to both givers and receivers. The donor, although providing nourishment, is making an impure offering; those who receive it are accepting improper sustenance. Any positive effect is outweighed by the negative one. Indeed, unless you have the power to resuscitate your victims on the spot, there is no situation in which the act of killing does not defile you as a negative action. You can also be sure that it will harm the lives and activities of the teachers.* If you are not capable of transferring beings’ consciousness to the state of great bliss, you should make every effort to avoid taking their lives.

(*Since spiritual guides appear according to the past actions of beings, the teacher and his disciples are indissolubly linked. Thus, if the disciples behave inappropriately, the effects rebound-in the relative sphere-on the teacher, reducing the period of his incarnation and creating obstacles for his activity for the benefit of others.)

To have wrong views, even for an instant, is to break all your vows and to cut yourself off from the Buddhist community. It also negates the freedom in this human existence to practise the Dharma. From the moment your mind is defiled by false views, even the good you do no longer leads to liberation, and the harm you do can no longer be confessed.*

(*Wrong views will render one’s attitude narrow. Even one’s positive actions will be limited in their effects because one does them without the motivation of attaining complete enlightenment for the sake of all beings. Moreover if one has no faith in those who transmit the Dharma one will not have the support for confession.)

2. The effects of the ten negative actions

Each negative act produces four kinds of karmic effect: the fully ripened effect, the effect similar to the cause, the conditioning effect and the proliferating effect.

2.1 THE FULLY RIPENED EFFECT*

(* This refers to the moment when the karmic energy produced by an action produces its maximum effect, which can be hastened or retarded by the effects of other actions.)

Committing anyone of the ten harmful acts while motivated by hatred brings about birth in the hells. Committing one of them out of desire leads to birth as a preta, and out of ignorance to birth as an animal. Once reborn in those lower realms, we have to undergo the sufferings particular to them.

Also, a very strong impulse – extremely powerful desire, anger, or ignorance-motivating a long and continuous accumulation of actions, causes birth in the hells. Should the impulse be less strong and the number of actions less, it causes rebirth as a preta; and if still less strong and numerous, as an animal.

2.2 THE EFFECT SIMILAR TO THE CAUSE

Even when we finally get out of the lower realm in which the fully ripened effect had caused us to be born, and obtain a human form, we go on experiencing the effect similar to the cause. In fact, in the lower realms, too, there are many different kinds of suffering that are similar to particular causes. These effects that are similar to the cause are of two kinds: actions similar to the cause and experiences similar to the cause.

2.2.1 Actions Similar to the Cause

This effect is a propensity for the same kind of actions as the original cause. If we killed before, we still like to kill; if we stole, we enjoy taking what is not given; and so forth. This explains why, for example, certain people from their earliest childhood kill all the insects and flies they see. Such a predilection for killing corresponds to similar acts performed in their past lives. From the cradle on, each of us acts quite differently, driven by different karmic urges. Some enjoy killing, some enjoy stealing, while others again feel no affinity for such actions and enjoy doing good instead.

All such tendencies are the residue of former actions, or in other words the effect similar to the cause. This is why it is said:

To see what you have done before, look at what you are now.

To see where you are going to be born next, look at what you do now.*

The same is true for animals, too. The instinct of animals such as falcons and wolves to kill, or of mice to steal, is in each case an effect similar to, and caused by, their former actions.

2.2.2 Experiences Similar to the Cause

Each of the ten harmful actions results in a pair of effects on our subsequent experiences.

Taking life. To have killed in a previous life makes our present life not only short, but also subject to frequent disease. Sometimes newborn babies die as an effect similar to the cause of having killed in a past life; for many lifetimes they may keep on dying as soon as they are born, over and over again. There are also people who survive into adulthood but from their earliest childhood are tormented by one illness after another without respite until their death, again as the result of having killed and assaulted others in a past life. In the face of such circumstances, it is more important to confess with regret the past actions that have brought them about than to find ways to modify each immediate problem. We should confess with regret and vow to renounce such actions; and, as an antidote to their effects, make efforts to undertake positive actions and abandon harmful ones.

Taking what is not given. To have stolen will make us not only poor, but also liable to suffer pillage, robbery or other calamities which disperse among enemies and rivals whatever few possessions we come by. For this reason, anyone who now lacks money or property would do better to create even a small spark of merit than to move mountains to get rich. If it is not your destiny to be wealthy because of your lack of generosity in past lives, no amount of effort in this life will help. Look at the loot most robbers or bandits get from each of their raids – often almost more than the very earth itself can hold. Yet people who live by robbery always end up dying of hunger. Notice, too, how traders or those who appropriate the goods of the Sangha fail to profit from their earnings, however great. On the other hand, people now experiencing the effects of their past generosity never lack wealth all their lives, and for many of them this happens without their making the least effort. So, if you have hopes of getting rich, devote your efforts to acts of charity and making offerings!

This continent of Jambudvipa gives a particular power* to the effects of actions, so that what we do early in life is likely to have an effect later in the same life-or even right away if done in certain exceptional circumstances. So to resort to theft, fraud or other ways of taking what is not given in the hopes of getting rich is to do just the opposite of what we had intended. The karmic effect will trap us in the world of the pretas for many kalpas. Even towards the end of this life, it will begin to affect us and will make us more and more impoverished, more and more troubled. We will be bereft of any control over the few possessions that remain to us. Our avarice will make us feel more and more destitute and deprived, however wealthy we may be. Our possessions will become the cause of harmful actions. We will be like pretas that guard treasures but are incapable of using what they possess. Look closely at people who are apparently rich. If they are not using their wealth freely for the Dharma, which is the source of happiness and well-being in this life and in lives to come, or even for food and clothing, they are actually poorer than the poor. Their preta-like experience right now is a karmic effect similar to the cause, resulting from their impure generosity in the past.**

(*A place where the force of karma is more powerful and its effects are felt more strongly and, in certain cases, sooner. Of the four continents in the universe of traditional cosmology, it is especially in Jambudvipa that actions produce strong effects, and in which individual experiences are more variable. The inhabitants of the other continents experience the results of past actions, for the most part, rather than creating new causes. Their experiences and lifespans are more fixed.)

(**Impure generosity is giving with a self-centered attitude, in a miserly fashion or halfheartedly, or giving and then regretting it afterwards. The effect of giving in that way is that one will be wealthy but will not benefit from it.)

Sexual misconduct. To have indulged in sexual misconduct, it is said, will cause us to have a spouse who is not only unattractive, but who also behaves in a loose or hostile manner. When couples cannot stop arguing or fighting, each partner usually lays the blame on the other’s bad character. In fact they are each experiencing the effect similar to the cause, resulting from their past sexual misconduct. Instead of hating each other, they should recognize that it is the effect of their past negative actions and be patient with each other. Lord Padampa Sangye says:

Families are as fleeting as a crowd on market-day;

People of Tingri, don’t bicker or fight!

Lying. The experience similar to the cause from having lied in past lives is that not only are we often criticized and belittled, but also we are often lied to by others. If you are falsely accused and criticized now, it is the effect of your having told lies in the past. Instead of getting angry and hurling insults at people who say such things about you, be grateful to them for helping you to exhaust the effects of many negative actions. You should feel happy. Rigdzin Jigme Lingpa says:

An enemy repaying your good with bad makes you progress in your practice.

His unjust accusations are a whip that steers you toward virtue. He’s the teacher who destroys all your attachment and desires.

Look at his great kindness that you never can repay!

Sowing discord. The effect similar to the cause of sowing discord is not only that our associates and servants cannot get along with each other, but also that they are argumentative and recalcitrant with us. For the most part the monks following lamas, the attendants of chiefs or the servants of householders do not get along well among themselves, and however many times they are asked to do something, they refuse to obey and argue defiantly. The hired servants of ordinary people pretend not to hear when asked to do chores, even easy ones. The master of the house has to repeat the order two or three times, and it is only when at last he gets angry and speaks harshly to them that they do what they were asked, slowly and grudgingly. Even when they have finished, they do not bother to come back and tell him. They are permanently in a bad mood. But the master is only reaping the fruits of the discord he has sown himself in the past. He should therefore regret his own negative actions, and work at reconciling his own and others’ disagreements.

Harsh words. To have spoken harsh words in past lives will not only make everything that is said to us offensive or insulting, but will also have the effect that everything we say provokes arguments.

Harsh language is the worst of the four negative actions of speech. As the proverb puts it:

Words have no arrows nor swords, yet they tear men’s minds to pieces.

To suddenly provoke hatred in another person, or-worse still-to say even a single offensive word to a holy being, causes many lifetimes to be spent in the lower realms without any chance of being released. It is said that a brahmin named Kapila once insulted the monks of the Buddha Kasyapa, calling them “horse-head,” “ox head” and many other such names. He was reborn as a fish-like sea monster with eighteen heads. He was not released from that state for an entire kalpa and even then was reborn in hell. A nun who called another nun a bitch was reborn herself as a bitch five hundred times. There are many similar stories. So learn to speak gently at all times. Moreover, since you never know who might be a holy being or a Bodhisattva, train yourself to perceive all beings purely. Learn to praise them and extol their good qualities and achievements. It is said that to criticize or speak offensively to a Bodhisattva is worse than killing all the beings in the three worlds:

To denigrate a Bodhisattva is a greater sin

Than killing all the beings in the three worlds;

All such great and futile faults that I have accumulated, I confess.

Worthless chatter. The effect similar to the cause of worthless chatter is not only that what we say will carry no weight, but also that we will lack any resolution or self-confidence. Nobody will believe us even when we speak the truth, and we will have no self-assurance when speaking in front of a crowd.

Covetousness. The effect of covetousness is not only to thwart whatever we most wish for, but also to bring about all the circumstances we want least.

Wishing harm on others. As the result of wishing harm on others, we will not only live in constant fear, but will also suffer frequent harm.

Wrong views. The effect of having harboured wrong views is that not only will we persist in such harmful beliefs, but also our mind will be disturbed by deceit and misconceptions.

2.3 THE CONDITIONING EFFECT

The conditioning effect acts on our environment. Taking life causes rebirth in grim, joyless landscapes full of mortally dangerous ravines and precipices. Taking what is not given causes rebirth in areas stricken by famine where frost and hail destroy crops and trees bear no fruit. Sexual misconduct obliges us to live in repulsive places, full of excrement and dung, muddy swamps, and so forth. Lying will bring us material insecurity, constant mental panic and encounters with terrifying things and situations. Sowing discord makes us inhabit regions difficult to cross, cut with deep ravines, rocky gorges and the like. Harsh speech causes rebirth in a bleak terrain, full of rocks, stones and thorns. Useless chatter causes rebirth on barren and infertile land which produces nothing in spite of being worked; the seasons are untimely and unpredictable. Covetousness will bring about poor harvests and all the many other ills of inhospitable places and times. Wishing harm on others leads to rebirth in places of constant fear with many different afflictions. Wrong views cause rebirth in impoverished circumstances without any refuge or protectors.

2.4 THE PROLIFERATING EFFECT

The proliferating effect is that whatever action we did before, we tend to repeat again and again. This brings an endless succession of suffering throughout all our subsequent lives. Our negative actions proliferate yet further and cause us to wander endlessly in samsara.

II. POSITIVE ACTIONS TO BE ADOPTED

In a general sense, the ten positive actions comprise the unconditional vow never to commit any of the ten negative actions, such as taking life, taking what is not given and so on, having understood their harmful effects.

To take such a vow in front of a teacher or preceptor is not strictly necessary; while to decide on your own to avoid all taking of life from now on, for example-or to avoid taking life in a particular place or at particular times, or to avoid killing certain animals – is in itself a positive act. However, making that promise in the presence of a teacher, a spiritual friend or a representation of the Three Jewels renders it particularly powerful.

It is not enough that you just happen to stop taking life, or stop the other negative actions. What counts is that you commit yourself with a vow to avoid that negative action, whatever happens. Thus even lay people who are unable to abstain completely from taking life can still derive great benefit from taking the vow not to kill for a period each year, either during the first month, the Month of Miracles; or during the fourth month, known as Vaisakha; or at each full or new moon, or for a particular year, month, or day.

Long ago, a village butcher made a vow in the presence of the noble Katyayana that he would not kill during the night. He was reborn in one of the ephemeral hells, where every day he was tormented all day long in a house of red-hot metal. But he spent every night in a palace, happy and comfortable, in the company of four goddesses.

The ten positive actions, then, consist of giving up the ten negative actions and practising their positive antidotes.

The three positive acts of the body are: (1) to renounce killing, and instead to protect the lives of living beings; (2) to renounce taking what is not given, and instead to practise generosity; and (3) to give up sexual misconduct, and instead to follow the rules of discipline.

The four positive acts of speech are: (1) to renounce lying, and instead to tell the truth; (2) to give up sowing discord, and instead to reconcile disputes; (3) to abandon harsh words, and instead to speak pleasantly; and (4) to put an end to useless chatter, and instead to recite prayers.

The three positive acts of the mind are: (1) to renounce covetousness, and instead to learn to be generous; (2) to give up wishing harm on others, and instead to cultivate the desire to help them; and (3) to put an end to wrong views, and instead to establish in yourself the true and authentic view.

The fully ripened effect of these acts is that you will be reborn in one of the three higher realms.

The effect similar to the cause as action is that you take pleasure in doing good in all your subsequent lives, so your merit goes on and on increasing.

The effects similar to the cause as experience for each of the ten are as follows: for giving up taking life, a long life with few illnesses; for giving up taking what is not given, prosperity and freedom from enemies or thieves; for giving up sexual misconduct, an attractive partner and few rivals; for renouncing lies, praise and love from everyone; for giving up sowing discord, a respectful circle of friends and servants; for giving up harsh words, hearing only pleasant speech; for giving up useless chatter, being listened to seriously; for abandoning covetousness, the fulfilment of your wishes; for giving up harmful thoughts, freedom from harm; and for giving up wrong views, the growth of the right view in your mind.

The conditioning effect is, in each case, the opposite of the corresponding negative effect: you are born in places that have all the most perfect circumstances.

The proliferating effect is that whatever good actions you do will multiply, bringing you uninterrupted good fortune.

III. THE ALL-DETERMINING QUALITY OF ACTIONS

In all their inconceivable variety, the pleasures and miseries that each individual being experiences-from the summit of existence down to the very lowest depth of hell-arise only from the positive and negative actions that each has amassed in the past. It is said in the Sutra of a Hundred Actions:

The joys and sorrows of beings

All come from their actions, said the Buddha.

The diversity of actions

Creates the diversity of beings

And impels their diverse wanderings.

Vast indeed is this net of actions!

Whatever strength, power, wealth or property we may now enjoy, none of it follows us when we die. We take with us only the positive and negative actions we have gathered during our lifetime, which then propel us onward to higher or lower samsaric realms. In the Sutra of Instructions to the King we read:

When the moment comes to leave, 0 King,

Neither possessions, friends nor family can follow.

But wherever beings come from, wherever they go,

Their actions follow them like their own shadow.

Tile effects of our positive or negative actions may not be immediately evident and identifiable; but nor do they just fade away. We will experience each one of them when the right conditions come together.

Even after a hundred kalpas

Beings’ actions are never lost.

When the conditions come together

Their fruit will fully ripen.

As the Sutra of a Hundred Actions says. And in the Treasury of Precious Qualities we find the following:

When the eagle soars up, high above the earth,

Its shadow for the while is nowhere to be seen;

Yet bird and shadow still are linked. So too our actions:

When conditions come together, their effects are clearly seen.

When a bird takes off and flies high up into the sky, its shadow seems to disappear. But that does not mean that the shadow no longer exists. Wherever the bird finally lands, there is its shadow again, just as dark and distinct as before. In the same way, even though our past good or bad actions may be invisible for the moment they cannot fail to come back to us in the end.

Indeed, how could this not be so for ordinary beings like us, when even Buddhas and Arhats, who have rid themselves of all karmic and emotional obscurations, still have to accept the effects of past actions?

One day the armies of Virudhaka, king of Sravasti, fell upon the city of the Sakyas* and massacred eighty thousand people. At that moment, the Buddha himself had a headache.

(*The Buddha’s clan, who lived on the borders of present-day India and Nepal.)

When his disciples asked him why this was, he replied:

“Many lifetimes ago, those Sakyas were fishermen who lived by killing and eating many fish. One day they caught two big ones, and instead of killing them immediately they left them tied to a pole. As those two fish stranded out of the water writhed in agony, they thought: ‘These men are killing us, although we have done them no harm. In return, may the day come when we kill them, without their having done us any harm.’ The effect of the two big fishes’ thought was that they were reborn as king Virudhaka and his minister Matropakara, while all the other fish killed by the fishermen became their troops. Today they have massacred the Sakyas.

“At that time, I myself was the child of one of those fishermen and, watching those two tied-up fish writhing in unbearable agony as they dried, I laughed. The effect of that action is that today I have a headache. But had I not achieved the qualities* I now possess, I, too, would have been killed by the troops of Virudhaka.”

(*The qualities of a Buddha: the thirty-two major and eighty minor marks, the ten powers, etc.)

On another occasion, the Buddha’s foot was injured by an acacia splinter – the result of his having killed Black Spearman during one of his previous lives as a Bodhisattva.

Maudgalyayana, of all the Buddha’s Sravaka disciples, possessed the greatest miraculous powers. Nonetheless, he was killed by the Parivrajikas, because of the power of his past actions. It happened as follows.

The sublime Sariputra and the great Maudgalyayana often used to travel to other worlds, such as the hell realms or the realm of the pretas, to work for the benefit of beings in those worlds. One day, while in the hells, they came across a tirthika teacher named Purnakasyapa who had been reborn there and was undergoing a multitude of different torments.

He said to them, “Noble ones, on your return to the human realm, please tell my former disciples that their guru, Purnakasyapa, has been reborn in hell. Tell them from me that the way of the Parivrajikas is not the way of virtue. The way of virtue lies in the doctrine of the Sakya Buddha. Our path is mistaken; they should abandon it and learn to follow Sakyamuni. And tell them, above all, that whenever they make offerings to the shrine they built for my bones, a shower of molten metal falls upon me. Tell them, I beg you, not to make those offerings any more.”

The two noble companions returned to the human realm. Sariputra arrived first and went to give the tirthikas their guru’s message but, the necessary karmic conditions being absent, they did not listen to him. When Maudgalyayana arrived, he asked Sariputra if he had taken to the tirthikas Purnakasyapa’s message.

“Yes,” replied Sariputra, “but they said not a word.”

Maudgalyayana said, “Since they cannot have taken in what you said, I shall speak to them myself.” And he went off to tell them what Purnakasyapa had said.

But the tirthikas were furious. “Not content with insulting us, he is criticizing our Guru!” they said. “Beat him!” They fell on him, beat him to a pulp, and left him lying there.

Now, until this point not even a concerted attack from all the three worlds together, let alone the blows of the Parivrajikas, could have harmed a single hair of Maudgalyayana’s head. But at that moment, crushed by the weight of his past actions, he succumbed like any ordinary man.

“I could not even think how to use magical powers, let alone do it,” he said. Sariputra wrapped him in his robes and carried him away.

When they came to the Jeta Grove Sariputra cried out, “Even to hear my friend’s death described would be unbearable! How can I watch it happen?” and he passed away into nirvana along with numerous other Arhats. Immediately afterwards, Maudgalyayana too passed beyond suffering.

Once in Kashmir there lived a monk called Ravati, who had many disciples. He was clairvoyant and had miraculous powers. One day he was dyeing his monk’s robes with saffron in a dense stretch of woodland. At the same time, a layman living nearby was searching for a calf that had strayed. He saw smoke rising up from the thick forest, and went to see what was going on.

Finding the monk stoking his fire, he asked: “What are you doing?”

“I’m dyeing my robes,” the monk replied.

The layman raised the lid off the cauldron of dye and looked inside.

“It’s meat!” he cried, and indeed when the monk looked in the cauldron he too saw what was inside as meat.

The layman led the monk off and handed him over to the king, saying, “Sire, this monk stole my calf. Please punish him.” The king had Ravati thrown into a pit.

However, several days later it happened that the layman’s cow found her missing calf by herself. The layman went back to see the king and said, “Sire, the monk did not steal my calf after all; please release him.”

But the king got distracted and forgot to have Ravati freed. For six months he did nothing about it.

Then one day a large group of the monk’s disciples, who had themselves attained miraculous powers, came flying through the air and landed in front of the king.

“Ravati is a pure and innocent monk,” they said to the king. “Please set him free.”

The king went to release the monk, and when he saw Ravati’s debilitated condition he was filled with great remorse.

“I meant to come sooner, but I left it so long,” he exclaimed. “I have committed a terrible sin!”

“No harm has been done,” said the monk. “It was all the fruit of my own deeds.”

“What kind of deeds?” asked the king.

“During a past life I was a thief, and once I stole a calf. When the owner came after me, I ran off, leaving the animal next to a pratyekabuddha who happened to be meditating in a thicket. The owner took the pratyekabuddha and threw him into a pit for six days. As the fully matured effect of my action, I have already been through numerous lives of suffering in the lower realms. The sufferings I have now just experienced in this life were the last of them.”

Another example is the story of the son of Surabhibhadra, an Indian king. One day, the prince’s mother gave him a seamless silken robe. He did not want to wear it immediately, saying, “I shall put it on the day I inherit the kingdom.”

“You never will inherit the kingdom,” said his mother. “That could only happen if your father, the king, died But your father and the teacher Nagarjuna have the same life force, so there is no chance that he will die as long as Nagarjuna is still alive. And since Nagarjuna has power over his own lifespan, your father will never die. That is why many of your elder brothers have already died without inheriting the kingdom.”

“So what can I do?” her son asked.

“Go to see the teacher Nagarjuna and ask him to give you his head. He will agree, because he is a Bodhisattva. I can see no other solution.”

The boy went to see Nagarjuna and asked him for his head. “Cut it off and take it,” the Master said. The boy took a sword and struck at Nagarjuna’s neck. But nothing happened. It was as if his blade had cut through thin air.

“Weapons cannot harm me,” the Master explained, “because five hundred lifetimes ago I entirely purified myself of all the fully maturing effects of having used weapons. However, I did kill an insect one day while cutting kusa grass. The full effect of that act has not yet played itself out, so if you use a blade of kusa grass you will be able to cut off my head.” Accordingly, the boy plucked a blade of kusa grass and severed Nagarjuna’s head, which fell to the ground. Nagarjuna entered nirvana saying,

Now I am leaving for the Blissful Land;

Later I shall return to this very body.*

(*According to legend, Nagarjuna’s head and body took the form of two large stones some distance apart (at Nagarjunakonda in South India) which gradually draw closer over the centuries. When they reunite, Nagarjuna will come to life again.)

If even exceptional individuals like these have to experience the effects of their own past actions, how can we whose negative actions amassed throughout beginningless time in our wanderings through the realms of samsara are already innumerable-ever hope to get free from samsara while we still go on accumulating them? Even to escape from the lower realms would be difficult. So let us at all costs avoid the slightest misdeed, however minute, and apply ourselves to doing whatever good we can, no matter how insignificant it may seem. As long as we are not making that effort, each instant of negative action is leading us into many kalpas of life in the lower worlds. Never underestimate the minutest wrong deed, thinking that it cannot do that much harm. As Bodhisattva Santideva says:

If evil acts of but a single instant

Lead to a kalpa in the deepest hell,

The evils I have done from time without beginning No need to say that they will keep me from the higher realms!

And in the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish we find:

Do not take lightly small misdeeds,

Believing they can do no harm:

Even a tiny spark of fire

Can set alight a mountain of hay.

In the same way, even the smallest positive acts bring great benefit. Do not disparage them, either, with the idea that there is not much point in doing them.

King Mandhatri in a past life was a poor man. One day, as he was on his way to a wedding with a fistful of beans in his hand, he met the Buddha Ksantisarana, who was travelling to the village. Moved by intense devotion, he threw him his beans. Four beans fell into the Buddha’s begging bowl and two others touched his heart. The maturation of this act was that he was reborn as the universal emperor over the continent of Jambu. Because of the four beans that fell into the bowl, he reigned over the four continents for eighty thousand years. Because of one of the two that touched his heart, he became sovereign over the realm of the Four Great Kings for another eighty thousand years; and because of the second, he shared equally with thirty-seven successive Indras their sovereignty over the Heaven of the Thirty-three.

It is also said that even to visualize the Buddha and throw a flower into the sky will result in your sharing Indra’s reign for a length of time difficult to imagine. This is why the Sutra of The Wise and the Foolish says:

Do not take lightly small good deeds,

Believing they can hardly help:

For drops of water one by one

In time can fill a giant pot.

And The Treasury of Precious Qualities says:

From seeds no bigger than a mustard grain

Grow vast ashota trees, which in a single year

Can put out branches each a league in length.

But even greater is the growth of good and evil.

The seed of the ashota tree is no bigger than a mustard seed, but the tree develops so quickly that its branches grow as much as a league in one year. Yet even this image is not adequate to describe the profuse growth of the fruit of positive and negative actions.

The tiniest transgression of the precepts, too, gives rise to great evils. One day Elapatra, king of the nagas, came to see the Buddha in the guise of a Universal Emperor.

The Buddha scolded him: “Isn’t the harm that you did to the teachings of the Buddha Kasyapa enough for you? Now do you want to harm mine too? Listen to the Dharma in your own real form!”

“Too many beings will hurt me if I do so,” replied the naga; so the Buddha placed him under the protection of Vajrapani, and he changed into a huge serpent, several leagues in length. On his head there grew a great elapatra tree, crushing him with its weight, its roots crawling with insects which caused him terrible suffering.

The Buddha was asked why he was like this, and replied, “Long ago, during the era of the Buddha Kasyapa’s teachings, he was a monk. One day his robe got caught on a big elapatra tree growing beside the path and was pulled off. He became extremely angry and, violating his precepts,” he cut the tree down. What you see today is the effect of that act.”

(*In addition to actions which are generally negative, there are actions which the Buddha proscribed for those who had taken particular vows. Here the monk is violating a precept forbidding fully ordained monks to cut vegetation.)

For all good or bad actions, the intention is by far the most important factor that determines whether they are positive or negative, heavy or light. It is like a tree: if the root is medicinal, the trunk and leaves will also be medicinal. If the root is poisonous, the trunk and leaves will be poisonous too. Medicinal leaves cannot grow from a poisonous root. In the same way, if an intention develops from aggression or attachment and is thus not entirely pure, the action that follows is bound to be negative, however positive it might seem. On the other hand, if the intention is pure, even acts that appear negative will in fact be positive. In the Treasury of Precious Qualities it says:

If a root is medicinal, so are its shoots.

If poisonous, no need to say its shoots will be the same.

What makes an act positive or negative is not how it looks

Or its size, but the good or bad intention behind it.

For this reason there are times when Bodhisattvas, the Heirs of the Conquerors, are permitted to actually commit the seven harmful acts of the body and speech, as long as their minds are pure, free from all selfish desire. This is illustrated by the examples of Captain Compassionate Heart who killed Black Spearman, or of the young brahmin Lover of the Stars who broke his vows of chastity with a young brahmin girl.

Once in a previous life, the Buddha was a captain called Compassionate Heart. He was sailing upon the ocean with five hundred merchants when the evil pirate called Black Spearman appeared, threatening to kill them all. The captain realized that these merchants were all non-returning Bodhisattvas,* and that if one man killed them all he would have to suffer in the hells for an incalculable number of kalpas. Moved by an intense feeling of compassion, he thought: “If I kill him, he will not have to go to hell. So I have no choice, even if it means that I have to go to hell myself.” With this great courage he killed the pirate, and in so doing gained as much merit as would normally take seventy thousand kalpas to achieve. On the face of it, the act was a harmful one, since the Bodhisattva was committing the physical act of murder. But it was done without the least selfish motivation. In the short term, it saved the lives of the five hundred merchants. And in the long term it saved Black Spearman from the sufferings of hell. In reality, therefore, it was a very powerful positive act.

(*Bodhisattvas who had reached a level where they were no longer obliged to return to samsaric existence.)

Again, there was a brahmin named Lover of the Stars who lived in the forest for many years, keeping the vow of chastity. One day he went begging in a village. A brahmin girl fell so hopelessly in love with him that she was about to kill herself. Moved by compassion towards her, he married her, which brought him forty thousand kalpas of merit.

Taking life or breaking one’s vow of chastity are permitted for such beings. On the other hand, the same acts done with selfish motivation, out of desire, hatred or ignorance, are not permitted for anyone.

A Bodhisattva with a vast mind and no trace of personal desire may also steal from the rich and miserly and, on their behalf, offer the goods to the Three Jewels or give them to the needy.

Lying in order to protect someone on the point of being killed, or to protect goods belonging to the Three Jewels, would also be permitted. But it is never right to deceive others in one’s own interest.

Sowing discord, for instance between two close friends, one of whom was a wrong-doer while the other loved to do good, would be permitted if there were a danger that the bad one’s stronger character would have corrupted the good one. However, it is not permissible simply to separate two people who get along well.

Harsh words could be used, for example, as a more forceful means to bring to the Dharma those on whom a softer approach makes no impression-or in advice given to a disciple in order to get at his hidden faults. As Atisa says:

The best teacher is one who attacks your hidden faults;

The best instruction is one aimed squarely at those hidden faults.

However, harsh words spoken just to insult others are not justified.

Worthless chatter might be used as a skilful means of introducing the Dharma to people who love talking and who cannot be brought to the Dharma otherwise. But it is never warranted simply to create distraction for oneself and others.

As for the three negative mental actions, they are never permitted for anyone because there is no way for intention to turn them into something positive. Once a negative thought has arisen it always develops into something negative.

The mind is the sole generator of good and bad. There are many occasions when the thoughts which arise in the mind, even if they are not translated into speech or action, have a very strong positive or negative effect. So always examine your mind. If your thoughts are positive, be glad and do more and more good. If they are negative, confess them immediately, feeling bad and ashamed that you still entertain such thoughts in spite of all the teaching you have received, and telling yourself that from now on you must do your utmost not to let such thoughts occur in your mind. Even when you do something positive, check your motivation carefully. If your intention is good, act. If your motivation is to impress people, or is based on rivalry or a thirst for fame, make sure you change it and infuse it with bodhicitta. If you are quite unable to transform your motivation, it would be better to postpone the meritorious act until later.

One day Geshe Ben was expecting a visit from a large number of his benefactors. That morning he arranged the offerings on his shrine in front of the images of the Three Jewels particularly neatly. Examining his intentions, he realized that they were not pure and that he was only trying to impress his patrons; so he picked up a handful of dust and threw it all over the offerings, saying, “Monk, just stay where you are and don’t put on airs!”

When Padampa Sangye heard this story, he said, “That handful of dust that Ben Kungyal threw was the best offering in all Tibet!”

So always watch your mind carefully. On our level, as ordinary beings, it is impossible not to have thoughts and actions which are inspired by evil intentions. But if we can recognize the wrong immediately, confess it and vow not to do it again, we will part company with it.

Another day, Geshe Ben was at the home of some patrons. At one moment his hosts left the room and the Geshe thought: “I have no tea. I’ll steal a bit to brew up when I get back to my hermitage.”

But the moment he put his hand in their bag of tea, he suddenly realized what he was doing and called to his patrons: “Come and look what I’m doing! Cut my hand off!”

Atisa said: “Since taking the pratimoksa vows, I have not been stained by the smallest fault. In practising the precepts of bodhicitta, I have committed one or two errors. And since taking up the Secret Mantra Vajrayana, even though I have sometimes stumbled, still, I have let neither faults nor downfalls remain with me for as much as a whole day.”

When he was travelling, as soon as any bad thought occurred to him he would take up the wooden mandala base* he carried with him and confess his bad thought, vowing never to let it happen again.

(*The circular base upon which piles of rice etc. are placed in the offering of the mandala. To make offerings is part of the process of purification.)

One day Geshe Ben was at a large gathering of geshes at Penyulgyal. After a while some curd was offered to the guests. Geshe Ben was seated in one of the middle rows, and noticed that the monks in the first row were receiving large portions.

“That curd looks delicious…” he thought to himself, “but I don’t think I’ll get my fair share.”

Immediately he caught hold of himself: “You yoghurt-addict!” he thought, and turned his bowl upside down. When the man who was serving the curd came and asked him if he would like some, he refused.

“This evil mind has already taken its share,” he said.

Although there was no wrong at all in wanting to share the feast equally with the other pure monks, it was the self-centredness of his expectant thoughts about getting that delicious curd that made him refuse it.

If you always examine your mind like this, adopting what is wholesome and rejecting what is harmful, your mind will become workable and all your thoughts will become positive.

Long ago, there was a brahmin called Ravi who examined his mind at all times. Whenever a bad thought arose, he would put aside a black pebble, and whenever a good thought arose he would put aside a white pebble. A first, all the pebbles he put aside were black. Then, as he persevered in developing antidotes and in adopting positive actions and rejecting negative ones, a time came when his piles of black and white pebbles were equal. In the end he had only white ones. This is how you should develop positive actions as an antidote with mindfulness and vigilance, and not contaminate yourself with even the smallest harmful actions.

Even if you have not accumulated negative actions during this present life, you cannot know the extent of all the actions you have accumulated in samsara which has no beginning, or imagine their effects which you have still to experience. There are therefore people who, although they now devote themselves entirely to virtue and the practice of emptiness, are nevertheless beset by sufferings. The effect of their actions that would otherwise have remained dormant but later would have resulted in their rebirth in the lower realms, surfaces because of the antidote that they are applying and ripens in this life. The Diamond Cutter Sutra says:

Bodhisattvas practising transcendent wisdom will be tormented-indeed, they will be greatly tormented-by past actions that would have brought suffering in future lives, but have ripened in this life instead.

Conversely, there are some people who only do harm, but who experience the fruit of some positive action right away, an action that would otherwise have ripened later on. This occurred in the land of Aparantaka. For seven days there was a rain of precious stones, then for seven days a rain of clothes, and for seven more days a rain of grain. In the end there was a rain of earth. Everyone was crushed to death and took rebirth in hell.

Such situations, in which those who do good suffer and those who do harm prosper, always occur as the result of actions done in the past. Your present actions, good or bad, will have their effects in your next life or in those to follow. For this reason it is vital to develop a firm conviction about the inevitable effect of your actions and always to behave accordingly.

Do not use the Dharma language of the highest views* to scorn the principle of cause and effect.

(*Using the Dharma language of the highest views to scorn the principle of cause and effect means to use the teaching of absolute truth as a pretext for doing whatever one wishes, saying there is no difference between good and bad, samsara and nirvana, Buddhas and ordinary beings, and so on.)

The Great Master of Oddiyana said:

Great King, in this Secret Mantrayana of mine, the view is the most important thing. However, do not let your action slip in the direction of the view. If it does, you will fall into the evil views of demons, prattling on about how goodness is empty, evil is empty. But do not let your view slip in the direction of action, either, or you will be caught in materialism and ideology,* and liberation will never come…

That is why my view is higher than the sky, but my attention to my actions and their effects is finer than flour.**

(*Matter and characteristics. This means that one will never get beyond a conceptual approach.)

(**Meticulous, precise.)

So however fully you have realized in your view the nature of reality, you must pay minute attention to your actions and their effects.

Someone once asked Padampa Sangye, “Once we have realized emptiness, does it still harm us to commit negative acts?”

“Once you realize emptiness,” Padampa Sangye replied, “it would be absurd to do anything negative. When you realize emptiness, compassion arises with it simultaneously.”

If you want to practise Dharma authentically, therefore, you should give priority to choosing what you do in accordance with the principle of cause and effect. View and action should be cultivated side by side. The sign that you have understood this teaching on the effects of actions is to be like Jetsun Milarepa.

His disciples said to him one day: “Jetsun, all the deeds that we see you doing are beyond the understanding of ordinary beings. Precious Jetsun, were you not an incarnation of Vajradhara, or of a Buddha or Bodhisattva right from the start?

“If you take me for an incarnation of Vajradhara, or of a Buddha or Bodhisattva,” the Jetsun replied, “it shows you have faith in me – but you could hardly have a more mistaken view of the Dharma! I started out by heaping up extremely negative acts, using spells and making hail. I soon realized that there was no way that I would not be reborn in hell. So I practised Dharma with relentless zeal. Thanks to the profound methods of the Secret Mantrayana, I have developed exceptional qualities in myself. Now, if you cannot develop any real determination to practise the Dharma, it is because you do not really believe in the principle of cause and effect. Anyone with a bit of determination could develop courage like mine if they had that true and heartfelt confidence in the effects of their actions. Then they would develop the same accomplishments – and people will think that they too are manifestations of Vajradhara, or of a Buddha or Bodhisattva.”

His belief in cause and effect utterly convinced Jetsun Mila that having committed the harmful acts of his youth he would be reborn in the hells. Because of that conviction, he practised with such determination that it is difficult to find any story either in India or Tibet to equal the tale of his trials and efforts.

So, arouse confidence from the depths of your heart in this crucial point, the principle of cause and effect. Always do as many good actions as possible, no matter how small, applying the three supreme methods. Promise yourself never to do the smallest negative act again, even if your life is at stake.

When you wake up in the morning, do not suddenly jump out of bed like a cow or a sheep from its pen. While you are still in bed, relax your mind; turn within and examine it carefully. If you have done anything negative during the night in your dreams, regret it and confess. On the other hand, if you have done something positive, be glad and dedicate the merit to the benefit of all beings. Arouse bodhicitta, thinking, “Today I will do whatever positive, good actions I can and do my best to avoid doing anything negative or evil, so that all infinite beings may attain perfect Buddhahood.”

At night, when you go to sleep, do not just drop off into unconsciousness. Take the time to relax in bed and examine yourself in the same way: “So, what use have I made of this day? What have I done that is positive?” If you have done some good, be glad and dedicate the merit so that all may attain Buddhahood. If you have done something wrong you should think, “How terrible I have been! I have just been destroying myself!” Confess it and vow never to act that way again.

At all times, be mindful and vigilant that you do not cling to your perceptions of the universe, and the beings within it, as real and solid. Train yourself to see everything as the play of unreal apparitions. To make your mind workable by always keeping it on a good and honest course is essentially the aim as well as the outcome of what we have been explaining, namely the practice of the four thoughts that turn the mind from samsara . In this way, all the good actions you do will automatically be linked to the three supreme methods. As it is said:

A person who does good is like a medicinal plant;

All who rely on him benefit.

A person who does harm is like a poisonous plant;

Those who rely on him are destroyed.

If you have the right state of mind yourself, you will be able to turn the minds of all those connected with you* towards the true Dharma. Immense merit for yourself and others will increase without limit. You will never again take rebirth in the lower worlds in which your prospects get worse and worse, but will always have the unique conditions of a god’s or human’s life. Even the region in which the holder of such a teaching dwells will have merit and good fortune and will always be protected by the gods.

(*This means whoever is connected with one in any way, positive, negative, or purely incidental. Even a minimal connection with a Bodhisattva, through seeing, hearing, touching, and so on, can bring great benefit and lead to liberation.)

I know all the details of karma, but I do not really believe in it.

I have heard a lot of Dharma, but never put it into practice.

Bless me and evil-doers like me

That our minds may mingle with the Dharma.

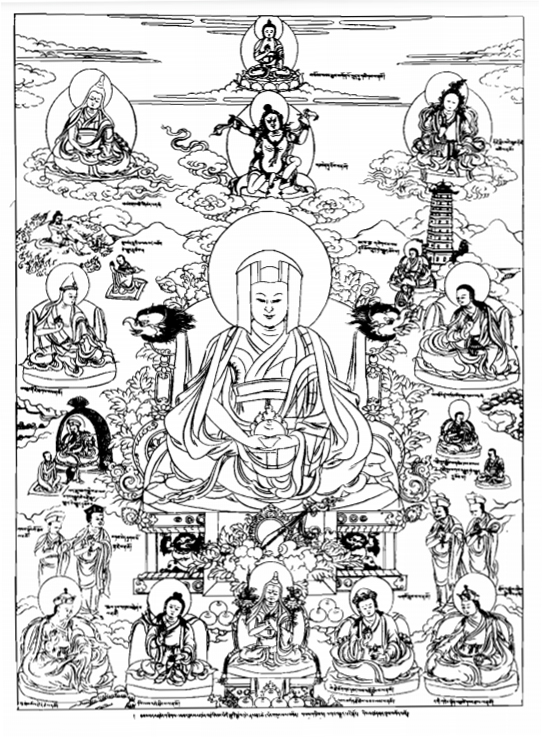

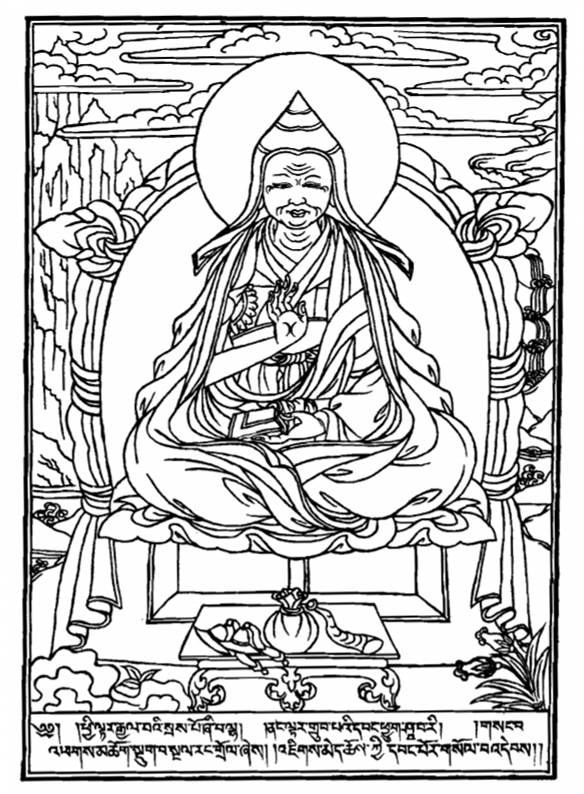

Gampopa (1079-1153)

(Also known as Dagpo Rinpoche. One of the principal disciples of Milarepa and an important master in many of the Kagyu lineages.)

Patrul Rinpoche (1808-1887)