Arousing Bodhicitta, the Root of the Great Vehicle

From Words of My Perfect Teacher:

Chapter 2

Arousing Bodhicitta, the Root of the Great Vehicle

Through your great wisdom, you have realized nirvana.

Through your great compassion, you willingly embrace samsdra.

Through your skill in methods you have realized that they are no different.

Peerless Teacher, at your feet I bow.

This chapter has three sections: training the mind in the four boundless qualities; arousing bodhicitta, the mind turned towards supreme enlightenment; and training in the precepts of bodhicitta in aspiration and bodhicitta in application.

I. TRAINING THE MIND IN THE FOUR BOUNDLESS QUALITIES

The four boundless qualities are boundless love, compassion, sympathetic joy and impartiality. Love is usually dealt with first. But when we practise the four one after the other as a training for the mind, we should start by developing impartiality. Otherwise, whatever love, compassion and sympathetic joy we generate will tend to be one-sided and not completely pure. In this case, therefore, we begin with the meditation on impartiality.

1. Meditation on impartiality

Impartiality means giving up our hatred for enemies and infatuation with friends, and having an even-minded attitude towards all beings, free of attachment to those close to us and aversion for those who are distant.

As things are now, we are very attached to those we think of as part of our own group – father and mother, relatives and so on – while we feel an intolerable aversion towards our enemies and those associated with them. This is a mistake, and comes from a lack of investigation.

In former lives, those whom we now consider our enemies have surely been close to us, ever lovingly at our side, looking after us with goodwill and giving us unimaginable help and support. Conversely, many of those whom we now call friends have certainly been against us and done us harm. As we saw in the chapter on impermanence, this is illustrated by the words of the sublime Katyayana:

He eats his father’s flesh, he beats his mother off,

He dandles on his lap his own unfortunate enemy;

The wife is gnawing at her husband’s bones.

I laugh to see what happens in samsara’s show!

Another example is the story of Princess Pema Sel, daughter of the Dharma King Trisong Detsen. When she died at the age of seventeen, her father went to ask Guru Rinpoche how such a thing could happen.

“I would have thought that my daughter must have been someone with pure past actions,” said the king. “She was born as the daughter of King Trisong Detsen. She met all of you translators and panditas, who are like real Buddhas. So how can it be that her life was nevertheless so short?”

“It was not at all because of any pure past deeds that the princess was born as your daughter,” the Master replied. “Once I, Padma, you, the great Dharma King, and the great Bodhisattva Abbot had been born as three low-caste boys. We were building the Great Stupa of Jarung Khashor. At that time the princess had taken birth as an insect, which stung you on the neck. Brushing it off with your hand, you accidentally killed it. Because of the debt you incurred in taking that life, the insect was reborn as your daughter.”*

(*An allusion to the story of the building of the Great Stupa, at Bodhnath, near Kathmandu, by a poultrywoman and her sons. Three of the sons were reborn, as a result of the wishes they made at that time, as the master Padmasambhava, the king Trisong Detsen, and the abbot Santaraksita, who together were responsible for firmly establishing the Dharma in Tibet. This magnificent stupa is a thriving focus for Tibetan devotees, who know it by the name Jarung Khashor.)

If even the children of Dharma King Trisong Detsen, who was Manjusri in person,* could be born to him in that way as the result of his past actions, what can one say about other beings?

(*Trisong Detsen is considered to be an emanation of the Bodhisattva Manjusri.)

At present we are closely linked with our parents and our children. We feel great affection for them and have incredible aspirations for them. When they suffer, or anything undesirable happens to them, we are more upset than we would be if such things had happened to us personally. All this is simply the repayment of debts for the harm we have done each other in past lives.

Of all the people who are now our enemies, there is not one who has not been our father or mother in the course of all our previous lives. Even now, the fact that we consider them to be against us does not necessarily mean that they are actually doing us any harm. There are some we think of as opponents who, from their side, do not see us in that way at all. Others might feel that they are our enemies but are quite incapable of doing us any real harm. There are also people who at the moment seem to be harming us, but in the long term what they are doing to us might bring us recognition and appreciation in this life, or make us turn to the Dharma and thus bring us much benefit and happiness. Yet others, if we can skilfully adapt to their characters and win them over with gentle words until we reach some agreement, might quite easily turn into friends.

On the other hand there are all those whom we normally consider closest to us – our children, for example. But there are sons and daughters who have cheated or even murdered their parents. Sometimes children side with people who have a dispute with their parents, and join forces with them to quarrel with their own family and plunder their wealth. Even when we get along well with those who are dear to us, their sorrows and problems actually affect us even more strongly than our own difficulties. In order to help our friends, our children and our other relatives, we pile up great waves of negative actions which will sweep us into the hells in our next life. When we really want to practise the Dharma properly they hold us back. Unable to give up our obsession with parents, children, and family, we keep putting off Dharma practice until later, and so never find the time for it. In short, such people may harm us even more than our enemies.

What is more, there is no guarantee that those we consider adversaries today will not be our children in future lives, or that our present friends will not be reborn as our enemies, and so on. It is only because we take these fleeting perceptions of “friend” and “enemy” as real that we accumulate negative actions through attachment and hatred. Why do we hold on to this millstone which will drag us down into the lower realms?

Make a firm decision, therefore, to see all infinite beings as your own parents and children. Then, like the great beings of the past whose lives we can read about, consider all friends and enemies as the same.

First, toward all those you do not like at all-those who arouse anger and hatred in you-train your mind by various means so that the anger and hatred you feel for them no longer arise. Think of them as you would of someone neutral, who does you neither good nor harm. Then reflect that the innumerable beings to whom you feel neutral have been your father or mother sometime during your past lives throughout time without beginning. Meditate on this theme, training yourself until you feel the same love for them as you do for your present parents. Finally, meditate until you feel the same compassion toward all beings-whether you see them as friends, enemies or in between-as you do for your own parents.

Now, it is no substitute for boundless impartiality just to think of everybody, friends and enemies, as the same, without any particular feeling of compassion, hatred or whatever. That is mindless impartiality, and brings neither harm nor benefit. The image given for truly boundless impartiality is a banquet given by a great sage. When the great sages of old offered feasts they would invite everyone, high or low, powerful or weak, good or bad, exceptional or ordinary, without making any distinction whatsoever. Likewise, our attitude toward all beings throughout space should be a vast feeling of compassion, encompassing them all equally. Train your mind until you reach such a state of boundless impartiality.

2. Meditation on love

Through meditating on boundless impartiality as described, you come to regard all beings of the three worlds with the same great love. The love that you feel for all of them should be like that of parents taking care of their young children. They ignore all their children’s ingratitude and all the difficulties involved, devoting their every thought, word and deed entirely to making their little ones happy, comfortable and cosy. Likewise, in this life and in all your future lives, devote everything you do, say or think to the well-being and happiness of all beings.

All those beings are striving for happiness and comfort. They all want to be happy and comfortable; not one of them wants to be unhappy or to suffer. Yet they do not understand that the cause of happiness is positive actions, and instead give themselves over to the ten negative actions. Their deepest wishes and their actions are therefore at odds: in their attempts to find happiness, they only bring suffering upon themselves.

Over and over again, meditate on the thought of how wonderful it would be if each one of those beings could have all the happiness and comfort they wish. Meditate on it until you want others to be happy just as intensely as you want to be happy yourself.

The sutras speak of “loving actions of body, loving actions of speech, loving actions of mind.” What this means is that everything you say with your mouth or do with your hands, instead of being harmful to others, should be straightforward and kind. As it says in The Way of the Bodhisattva:

Whenever catching sight of others,

Look on them with open, loving heart.

Even when you simply look at someone else, let that look be smiling and pleasant rather than an aggressive glare or some expression of anger. There are stories about this, like the one about the powerful ruler who glared at everyone with a very wrathful look. It is said that he was reborn as a preta living on left-overs under the stove of a house, and after that, because he had also looked at a holy being in that way, he was reborn in hell.

Whatever actions you do with your body, try to do them gently and pleasantly, endeavouring not to harm others but to help them. Your speech should not express such attitudes as contempt, criticism or jealousy. Make every single word you say pleasant and true. As for your mental attitude, when you help others do not wish for anything good in return. Do not be a hypocrite and try to make other people see you as a Bodhisattva because of your kind words and actions. Simply wish for others’ happiness from the bottom of your heart and only consider what would be most beneficial for them. Pray again and again with these words: “Throughout all my lives, may I never harm so much as a single hair on another being’s head, and may I always help each of them.”

It is particularly important to avoid making anyone under your authority suffer, by beating them, forcing them to work too hard and so on. This applies to your servants and also to your animals, right down to the humblest watchdog. Always, under all circumstances, be kind to them in thought, word and deed. To be reborn as a servant, or as a watchdog for that matter, and to be despised and looked down upon by everyone, is the maturation of the effects of past actions. It is the reciprocal effect of having despised and looked down on others while in a position of power in a past life. If you now despise others because of your own power and wealth, you will repay that debt in some future life by being reborn as their servants. So be especially kind to those in a lower position than yourself.

Anything you can do physically, verbally or mentally to help your own parents, especially, or those suffering from chronic ill health, will bring inconceivable benefits. Jowo Atisa says:

To be kind to those who have come from afar, to those who have been ill for a long time, or to our parents in their old age, is equivalent to meditating on emptiness of which compassion is the very essence.

Our parents have shown us such immense love and kindness that to upset them in their old age would be an extremely negative act. The Buddha himself, to repay his mother’s kindness, went to the Heaven of the Thirty three to teach her the Dharma. It is said that even if we were to serve our parents by carrying them around the whole world on our shoulders, it would still not repay their kindness. However, we can repay that kindness by introducing them to the Buddha’s teaching. So always serve your parents in thought, word and deed, and try to find ways to bring them to the Dharma.

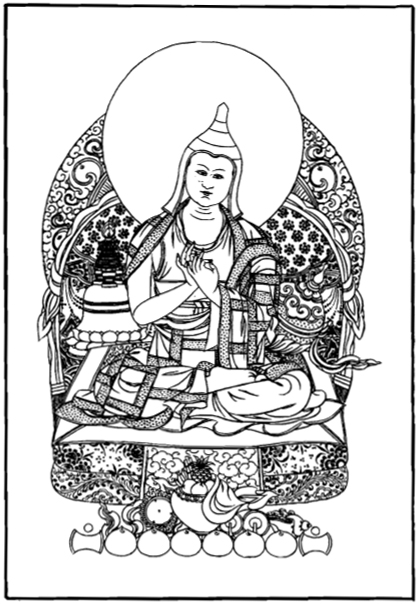

The Great Master of Oddiyana said:

Do not make old people distressed; look after them with care and respect.

In whatever you say and do, be kind to all those older than you. Take care of them and do whatever you can to please them.

Nowadays most people say that there is no way to get on in the samsaric world without harming others. But this is not true.

Long ago, in Khotan, two novices were meditating on the sublime Manjusri.

One day, he appeared to them and said, “There is no karmic link between you and me. The deity with whom you have had a connection in your past lives is the great Avalokitesvara. He is at present to be found in Tibet, over which he rules as the king.* You should go there to see him.”

(*The king was Songtsen Gampo, the first Buddhist king of Tibet, who is considered to be an incarnation of Avalokitesvara.)

When the two novices arrived in Tibet and went within the walls of Lhasa, they could see that a large number of people had been executed or imprisoned. They asked what was going on.

“Those are punishments ordered by the king,” they were told.

“This king is most certainly not Avalokitesvara,” they said to themselves, and fearing that they might well be punished too, they decided to run away.

The king knew that they were leaving and sent a messenger after them summoning them to his presence.

“Do not be afraid,” he told them. “Tibet is a wild land, hard to subjugate. For that reason I have had to produce the illusion of prisoners being executed, dismembered, and so on. But in reality, I have not harmed a single hair on anyone’s head.”

That king was the ruler of all Tibet, the Land of Snows, and brought kings in all four directions under his power. He vanquished invading armies and kept peace along the frontiers. Although he was obliged to conquer enemies and defend his subjects on such a vast scale, he managed to do so without harming so much as a hair on a single being’s head. How could it not be possible for us, therefore, to avoid harming others as we look after our own tiny dwellings, which by comparison are no bigger than insects’ nests?

Harming others brings harm in return. It just creates endless suffering for this life and the next. No good can ever come of it, even in the things of this life. No-one ever gets rich from murder, theft, or whatever it might be. They only end up paying the penalty and losing all their money and possessions in the process.

The image given for boundless love is a mother bird taking care of her chicks. She starts by making a soft, comfortable nest. She shelters them with her wings, keeping them warm. She is always gentle with them and she protects them until they can flyaway. Like that mother bird, learn to be kind in thought, word and deed to all beings in the three worlds.

3. Meditation on compassion

The meditation on compassion is to imagine beings tormented by cruel suffering and to wish them free from it. As it is said:

Think of someone in immense torment-a person cast into the deepest dungeon awaiting execution, or an animal standing before the butcher about to be slaughtered. Feel love towards that being as if it were your own mother or child.

Imagine a prisoner condemned to death by the ruler and being led to the place of execution, or a sheep being caught and tied up by the butcher.

When you think of a condemned prisoner, instead of thinking of that suffering person as someone else, imagine that it is you. Ask yourself what you would do in that situation. What now? There is nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. No refuge and no-one to protect you. You have no means of escape. You cannot flyaway. You have no strength, no army to defend you. Now, at this very moment, all the perceptions of this life are about to cease. You will even have to leave behind your own dear body that you have sustained with so much care, and set out for the next life. What anguish! Train your mind by taking the suffering of that condemned prisoner upon yourself.

And when you think of a sheep being led to the slaughter, do not think of it as just a sheep. Instead, feel sincerely that this is your own old mother that they are about to kill, and ask yourself what you would do in such a situation. What are you going to do now that they are going to kill your old mother, even though she has done no harm? Experience in the depth of your heart the kind of suffering that your mother must be going through. When your heart is bursting with the desire to do something right away to prevent your old mother from being butchered on the spot, reflect that although this suffering creature is not actually your father or mother in this present life, it is sure to have been your parent at some time in your past lives and to have brought you up with great kindness in just the same way. So there is no real difference. Alas for your poor parents who are suffering so much! If only they could be free from their distress right now, without delay-this very instant! With these thoughts in your heart, meditate with such unbearable compassion that your eyes fill with tears.

When your compassion is aroused, think how all this suffering is the effect of harmful actions committed in the past. All those poor beings now indulging in harmful actions will inevitably have to suffer too. With this in mind, meditate with compassion on all beings who are creating causes of suffering for themselves by killing and other harmful actions.

Then consider the suffering of all beings born in the hells, among the pretas and other realms of torment. Identify with them as if they were your parents, or yourself, and meditate on compassion with great energy.

Finally, reflect deeply upon all beings in the three worlds. Wherever there is space there are beings. Wherever there are beings, there are negative actions and the resulting suffering. Poor beings, involved only in all that negative action and suffering! How wonderful it would be if each individual being of the six realms could be free from all the perceptions brought about by past actions, all those sufferings and negative tendencies, and attain the everlasting happiness of perfect Buddhahood.

When you start meditating on compassion, it is important to focus first on suffering beings individually, one at a time, and only then to train yourself step by step until you can meditate on all beings as a whole. Otherwise your compassion will be vague and intellectual. It will not be the real thing.

Reflect particularly on the sufferings and hardships of your own cattle, sheep, packhorses and other domestic animals. We inflict all sorts of barbarity on such creatures, comparable to the torments of hell. We pierce their noses, castrate them, pull out their hair and bleed them alive.* Not even for a moment do we consider that these animals might be suffering. If we think about it carefully, the trouble is that we have not cultivated compassion. Think about it carefully: right now, were someone to pull out a single strand of your hair you would cry out in pain-you would not put up with it at all. Yet we twist out all the long belly-hairs of our yaks, leaving a red weal of bare flesh behind, and from where each hair was growing a drop of blood begins to flow. Although the beast is grunting with pain, it never crosses our mind that it is suffering.

(*The softer belly hair of the yak, used as wool, is pulled out rather than shorn. Blood from living yaks is used to make sausages.)

We cannot stand having a blister on our hand. Sometimes when our backsides hurt from travelling on horseback we can no longer sit in the saddle and have to ride sidesaddle instead. But it never occurs to us that the horse might be weary or suffering. When it can no longer go on and it stumbles, panting for breath, we still think that it is just being stubborn. We lose our temper and thrash it without a moment’s sympathy.

Think of an individual animal-a sheep, for example-that is being slaughtered. First, as it is dragged from the flock, it is struck with paralyzing fear. A blood-blister comes up where it has been grabbed. It is thrown on its back; its feet are tied together with a leather thong and its muzzle bound till it suffocates.* If, in the throes of its agony, the animal is a little slow in dying, the butcher, that man of evil actions, just gets irritated.

“Here’s one that doesn’t want to die!” says he, and hits it.

Hardly is the sheep dead than it is already being skinned and gutted.

(*In Tibet, it is common to slaughter animals by suffocation.)

At the same time another beast is being bled till it cannot walk straight. The blood of the dead animal is mixed with the blood of the living one and the mixture is cooked up as sausages in the entrails of the one already disembowelled.* Anyone who can eat such things afterwards must be a real cannibal.

(*As blood-sausages. This follows a local belief that a mixture of the blood of a living animal and the blood of a dead one increases vitality.)

Think carefully about the suffering of these animals. Imagine that you yourself are undergoing that suffering and see what it is like. Cover your mouth with your hands and stop yourself breathing. Stay like that for a while. Experience the pain and the panic. When you have really seen what it is like, think again and again how sad it is that all those beings are afflicted by such terrible sufferings without a moment’s respite. If only you had the power to give them refuge from all these sufferings!

Lamas and monks are the people who are supposed to have the most compassion. But they have none at all. They are worse than householders when it comes to making beings suffer. This is a sign that the era of the Buddha’s teaching is really approaching its end. We have reached a time when flesh-eating demons and ogres are given all the honours. In the past, our Teacher, Sakyamuni, rejected the kingdom of a universal monarch* as though it were so much spit in the dust, and became a renunciate. With his Arhat followers he went on foot, begging for alms, bowl and staff in hand. Not only did they do without packhorses and mules, but even the Buddha himself had no mount to ride. That was because he felt that to make another being suffer was not the way of the Buddhist teaching. Could the Buddha really not have been resourceful enough to find himself an old horse to ride?

(*According to the predictions of a brahmin astrologer after the birth of the prince Siddhartha, the child would become either a universal monarch or a Buddha.)

Our own venerables, however, as they set out for a village ceremony, push a piece of rough twine through the ring-hole gouged in their yak’s muzzle. Once they are hoisted into the saddle, they pull with both hands as hard as they can on the yak-hair cord, which digs into the animal’s nostrils, causing unbearable pain and making the poor creature rear and plunge. So the rider, with all his strength, whacks it with his whip. Unable to stand this new pain on its flanks, the yak starts to run-but is pulled up again by the nose. The pain in its nostrils is now so unbearable that it stops in its tracks, and has to be whipped again. A tug in front, a whack behind, until soon the animal is aching and exhausted. Sweat drips from every hair, its tongue hangs out, its breath rasps, and it can no longer go on.

“What’s the matter with him? He’s still not moving properly,” the rider thinks and, getting angry, digs the beast in the flanks with his whip handle, until in his rage he digs it in so hard that the handle breaks in two. He stuffs the pieces in his belt, picks up a sharp stone and, turning round in the saddle, slams it down hard on to the old yak’s rump … all this because he feels not the slightest compassion for the animal.

Imagine yourself as an old yak, your back weighed down with a load far too heavy, a rope pulling you by the nostrils, your flanks whipped, your ribs bruised by the stirrups. In front, behind, and on both sides you feel only burning pain. Without a second’s rest, you go up long slopes, down steep descents, you cross wide rivers and broad plains. With no chance to swallow even a mouthful of food, you are driven on against your will from the early dawn until late in the evening when the last glimmers of the setting sun have disappeared. Reflect on how difficult and exhausting it would be, what pain, hunger and thirst you would experience, and then take that suffering upon yourself. You cannot but feel intense and unbearable compassion.

Normally, those we call lamas and monks ought to be a refuge and a help-impartial protectors and guides of all beings. But in fact, they favour their patrons, the ones who give them food and drink and make offerings to them. They pray that these particular individuals may be sheltered and protected. They give them empowerments and blessings. And all the while they are ganging up to cast out all the pretas and mischievous spirits whose evil rebirth is the result of their unfortunate karma. The lamas performing such ceremonies work themselves up into a fury and make beating gestures, intoning, “Kill, kill! Strike, strike!”

Now surely, if anyone takes harmful spirits as something to be killed or beaten, it must be because his mind is under the power of attachment and hatred and he has never given rise to vast, impartial compassion. When you think about it carefully, those malignant spirits are far more in need of compassion than any benefactors. They have become harmful spirits because of their evil karma. Reborn as pretas, with horrible bodies, their pain and fear is unimaginable. They experience nothing but endless hunger, thirst and exhaustion. They perceive everything as threatening. As their minds are full of hate and aggression, many go to hell as soon as they die. Who could deserve more pity? The patrons may be sick and suffering, but that will help them to exhaust their evil karma, not to create more. Those evil spirits, on the other hand, are harming others with their evil intentions, and will be hurled by those harmful actions to the depths of the lower realms.

If the Conqueror, skilled in means and full of compassion, taught the art of exorcising or intimidating these harmful spirits with violent methods, it was out of compassion for them, like a mother spanking a child who will not obey her. He also permitted the ritual of liberation to be practised by those who have the power to interrupt the flow of evil deeds of beings who only do harm, and to transfer their consciousness to a pure realm. But as for pandering to benefactors, monks and others that we consider to be on our own side, and rejecting demons and wrongdoers as hateful enemies-protecting the one and attacking the other out of attachment and hatred-were such attitudes what the Conqueror taught? As long as we are driven by such feelings of attachment and hatred, it would be futile to try to expel or attack any harmful spirits. Their bodies are only mental and they will not obey us. They will only do us harm in return. Indeed-not to speak of desire and hate-as long as we even believe that such gods and spirits really exist and want them to go away, we will never subdue them.

When Jetsun Mila was living in the Garuda Fortress Cave in the Chong valley, the king of obstacle-makers, Vinayaka, produced a supernatural illusion. In his cave, jetsun Mila found five atsaras* with eyes the size of saucers. He prayed to his teacher and to his yidam, but the demons did not go away. He meditated on the visualization of his deity and recited wrathful mantras, but still they would not go.

(*Is a corruption of the Sanskrit acarya, and here means apparitions taking the form of Indian ascetics.)

Finally, he thought, “Marpa of Lhodrak showed me that everything in the universe is mind, and that the nature of mind is empty and radiant. To believe in these demons and obstacle-makers as something external and to want them to go away has no meaning.”

Feeling powerful confidence in the view that knows spirits and demons to be simply one’s own perceptions, he strode back into his cave. Terrified and rolling their eyes, the atsaras disappeared.

This is also what the Ogress of the Rock meant, when she sang to him:

This demon of your own tendencies arises from your mind;

If you don’t recognize the nature of your mind,

I’m not going to leave just because you tell me to go.

If you don’t realize that your mind is void,

There are many more demons besides myself!

But if you recognize the nature of your own mind,

Adverse circumstances will serve only to sustain you

And even I, Ogress of the Rock, will be at your bidding.

How, then, instead of having confidence in the view that recognizes all spirits and demons as being one’s own mind, could we subjugate them by getting angry?

When clerics visit their patrons, they happily eat all the sheep that have been killed and served to them, without the least hesitation. When they perform special rituals to make offerings to the protectors, they claim that clean meat is needed as an ingredient. For them, this means the still bleeding flesh and fat of a freshly killed animal, with which they decorate all the tormas and other offerings. Such fearful methods of intimidation can only be Bonpo or tirthika rites-they are certainly not Buddhist. In Buddhism, once we have taken refuge in the Dharma we have to give up harming others. How could having an animal killed everywhere we go, and enjoying its flesh and blood, not be a contravention of the precepts of taking refuge? More particularly, in the Bodhisattva tradition of the Great Vehicle, we are supposed to be the refuge and protector of all infinite beings. But for those very beings with unfortunate karma that we are supposed to be protecting we feel not the slightest shred of compassion. Instead, those beings under our protection are murdered, their boiled flesh and blood set before us, and their protectors-we Bodhisattvas-then gleefully gobble it all up, smacking our lips. Could anything be more vicious and cruel?

The texts of the Secret Mantra Vajrayana say:

For whatever we have done to upset the simha and tramen*

By not gathering offerings of flesh and blood according to the texts,

We beg the dakinis of the sacred places to forgive us.

(*Symbolic deities of the mandala.)

Now here, “gathering offerings of flesh and blood according to the texts” means to gather them as explained in the tantric texts of the Secret Mantrayana. What are the directives in those texts?

The five types of meat and five ambrosias

Are the food and drink of the outer feast gathering.

Offering a feast of flesh and blood according to the texts, therefore, means offering the five meats considered worthy samaya substances for the Secret Mantrayana – namely, the flesh of humans, horses, dogs, elephants and cows. These five kinds of meat are undefiled by harmful action because these are all creatures which are not killed for food.* This is quite the opposite of sticking to concepts of clean and unclean in which human flesh, the flesh of dogs and the like are seen as unclean and inferior, and the succulent, fatty meat of an animal that has just been killed for food is seen as clean. Such attitudes are referred to as:

Viewing the substances of the five samayas of relishing

As pure and impure, or consuming them heedlessly.

(*Different tantras include lions or peacocks in the list instead of dogs or cows. All of these are types of meat that were not normally eaten because they were taboo according to brahmanical thought in ancient India, being either too holy or else unclean. They are therefore specified for practices aiming to break concepts.)

In other words, having ideas of pure and impure which transgress the samayas of relishing. Even those five acceptable kinds of meat may only be used if you have the power to transform the food you eat into ambrosia and if you are in the process of practising to attain particular accomplishments in a solitary place. To eat them casually in the village, just because you like the taste, is what is meant by “heedless consumption contrary to the samayas of relishing,” and is also a transgression.

“Pure meat,” therefore, does not mean the meat of an animal slaughtered for food, but “the meat of an animal that died because of its own past actions,” meaning meat from an animal that died of old age, sickness, or other natural causes that were the effect of its own past actions alone.

The incomparable Dagpo Rinpoche said that taking the still warm flesh and blood of a freshly slaughtered animal and placing it in the mandala would make all the wisdom deities faint. It is also said that offering to the wisdom deities the flesh and blood of a slaughtered animal is like murdering a child in front of its mother. If you invited a mother for a meal and then set before her the flesh of her own child, would she like it, or would she not like it? It is with the same love as a mother for her only child that the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas look on all beings of the three worlds. Slaughtering an innocent animal that has been the victim of its own bad actions and offering its flesh and blood to them is therefore no way to please them. As the Bodhisattva Santideva says:

Just as no pleasures can bring delight

To someone whose body is ablaze with fire,

Nor can the great compassionate ones be pleased

When harm is done to sentient beings.

If you perform rituals like the offering prayer to the protectors using only the flesh and blood of slain animals, it goes without saying that the wisdom deities and the protectors of the Buddha’s doctrine, who are all pure Bodhisattvas, will never accept those offerings of slaughtered beings laid out like meat on a butcher’s counter. They will not even come anywhere near. Instead, powerful evil spirits who like warm flesh and blood and are ever eager to do harm will gather round the offering and feast on it.

For a short while after a practitioner of such “red offerings” has done his work, people may notice some minor benefits. But since the spirits involved are constantly harming others, they are liable to cause sudden problems and sicknesses. Again the practitioner of the “red” rituals will make his appearance and offer flesh and blood, and again that will help for a little while. This is how evil spirits and practitioners of the red rites become inseparable companions who always support each other. Like beasts of prey on the prowl, they roam around, obsessed solely by their urge to consume flesh, gnaw bones, and seek ever more victims. Possessed by evil spirits, practitioners of such rituals lose whatever disillusionment with samsara and thirst for liberation they may have had before. Whatever faith, purity of perception and interest in Dharma they once had, these qualities all fade away until the point comes when even the Buddha himself flying in the sky before them would arouse no faith in them, and even the sight of an animal with all its innards hanging out would arouse no compassion. They are always on the lookout for prey, like killer raksasas marching to war, their faces inflamed, shaking with rage and bristling with aggression. They pride themselves on the power and blessing of their speech, which comes from their intimacy with evil spirits. As soon as they die they are catapulted straight into hell-unless their negative actions are still not yet quite sufficient for that, in which case they are reborn in the entourage of some evil spirit preying on the life force of others, or as hawks, wolves and other predators.

During the reign of Dharma King Trisong Detsen, the Bonpos made offerings of blood and meat for the king’s benefit. The Second Buddha from Oddiyana, the great pandita Vimalamitra, the great Bodhisattva Abbot and the other translators and panditas were all completely outraged at the sight of the Bonpos’ offerings. They said:

A single teaching cannot have two teachers;

A single religion cannot have two methods of practice.

The Bon tradition is opposed to the law of Dharma;

Its evil is even worse than ordinary wrongdoing.

If you permit such practices, we shall go back home.

The panditas were all of the same opinion without even having to discuss the matter. When the king asked them to preach the Dharma, not one of them came forward. Even when he served them food, they refused to eat.

If we, claiming to walk in the footsteps of the panditas, siddhas and Bodhisattvas of the past, now perform the profound rites of the Secret Mantrayana in the manner of Bonpos and cause harm to beings, it will destroy the sublimity of the doctrine and dishonour the Three Jewels, and will cast both ourselves and others into the hells.

Always take the lowest place. Wear simple clothes. Help all other beings as much as you can. In everything you do, simply work at developing love and compassion until they have become a fundamental part of you. That will serve the purpose, even if you do not practise the more outward and conspicuous forms of Dharma such as prayers, virtuous activities and altruistic works. The Sutra that Perfectly Encapsulates the Dharma says:

Let those who desire Buddhahood not train in many Dharmas but only one.

Which one? Great compassion.

Those with great compassion possess all the Buddha’s teaching as if it were in the palm of their hand.

Geshe Tonpa was visited once by a monk who was a disciple of the Three Brothers and Khampa Lungpa.

“What is Potowa doing nowadays?” Tonpa asked the monk.

“He is teaching the Dharma to hundreds of members of the Sangha.”

“Wonderful! And what about Geshe Puchungwa?”

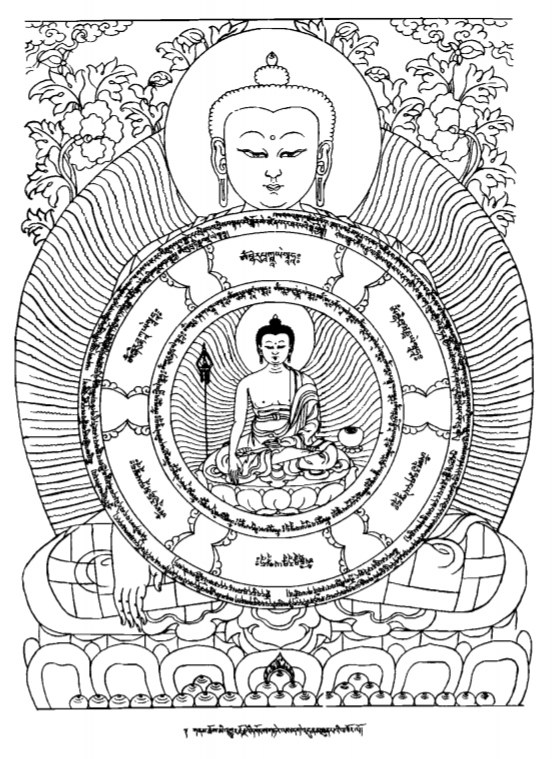

“He spends all his time fashioning representations* of the body, speech and mind of the Buddha from materials that he and other people have offered.”

“Wonderful!” Geshe Tonpa repeated. “What about Gonpawa?”

“He does nothing but meditate.”

“Wonderful! Tell me about Khampa Lhungpa.”

“He stays in solitude, weeping continually, with his face hidden.”

At this Tonpa took off his hat, joined his hands before his heart and, shedding many tears, exclaimed, “Oh, that is really marvellous! That is really practising the Dharma. I could tell you a lot about how good he is, but I know he wouldn’t like it.”

The reason why Khampa Lhungpa hid his face and cried all the time was that he was constantly thinking about beings tortured by the sufferings of samsara, and meditating on compassion for them.

(*Lit. support. The representations of the Buddha’s body refer to statues and paintings, of his speech to sacred texts and other writings, and of his mind to stupas.)

One day Chengawa was explaining the numerous reasons why love and compassion were so important, when Langri Thangpa prostrated himself before him and said that thenceforth he would meditate on nothing but those two things. Chengawa bared his head and said three times, “What excellent news!”

Nothing could be more effective than compassion for purifying us of negative actions and obscurations. Once long ago, in India, the Abhidharma teaching had been challenged on three separate occasions and was about to disappear. But a brahmin nun named Prakasasila had the thought, “I have been born as a woman. Because of my low status I cannot myself make the Buddha’s doctrine shine forth. So I will couple with men and give birth to sons who can spread the teaching of the Abhidharma.”

With a ksatriya as the father she gave birth to the noble Asanga, and with a brahmin to Vasubandhu. As each of her two sons came of age, they asked what their fathers’ work had been.

Their mother told each of them, “I did not give birth to you to follow in your father’s footsteps. You were born to spread the Buddha’s teachings. You must study the Dharma, and become teachers of the Abhidharma.”

Vasubandhu went off to Kashmir to study Abhidharma with Sanghabhadra. Asanga went to Kukkutapada Mountain, where he started to do the practice of the Buddha Maitreya in the hopes that he might have a vision of him and ask him for instruction. Six years passed, and although he meditated hard he did not have as much as a single auspicious dream.

“Now it looks as if I will never succeed,” he thought, and departed, feeling discouraged. Along the way, he came across a man rubbing an enormous iron bar with a soft cotton cloth.

“What are you trying to do, rubbing like that?” he asked the man.

The man replied, “I need a needle, so I’m making one by rubbing away at this bar.”

Asanga thought, “He’ll never make a needle by rubbing that huge bar with a soft piece of cotton. Even if it could be done in a hundred years, will he live that long? If ordinary people make such efforts for so little reason, I can see that I have never really practised the Dharma with any persistence.”

So he went back to his practice. He practised for three more years, still with no sign.*

(*Certain experiences such as visions, dreams etc. may be, but are not necessarily, signs of progress in the practice. Teachers in Patrul Rinpoche’s lineage insist that one should not be fascinated by such experiences. One should rather measure progress by the growth of devotion, compassion and freedom from negative emotions in one’s mind.)

“This time I’m quite certain that I can never succeed,” he said, and he took to the road again. He came at last to a rock so high that it seemed to touch the heavens. At its foot, a man was stroking it with a feather dipped in water.

“What are you doing?” Asanga asked him.

“This rock is too tall,” the man said. “I don’t get any sun on my house, which is to the west of it. So I’m going to wear it away till it disappears.”

Asanga, with the same thoughts as three years before, went back and practised for another three years, still without so much as a single good dream.

Utterly discouraged, he said “Now whatever I do I can never succeed!” and set off once more.

Along the road, he came across a bitch with two crippled hind legs and her entire hind quarters crawling with maggots. Nevertheless, she was still full of aggression, and tried to bite him as she dragged herself along on her forelegs, the rest of her body trailing along on the ground behind her. Asanga was swept by deep, unbearable compassion. Cutting off a piece of his own flesh, he gave it to the bitch to eat. Then he decided that he had to rid her of the worms on her hind quarters. Fearing that he might kill them if he removed them with his fingers, he realized that the only way to do it was with his tongue. But whenever he looked at the whole of the creature’s body, so rotten and full of pus, he could not bring himself to do it. So he shut his eyes and stretched out his tongue…

Instead of touching the body of the bitch, his tongue touched the ground.

He opened his eyes and found that the bitch had disappeared. In its place stood Lord Maitreya, surrounded by a halo of light.

“How unkind you are,” Asanga cried, “not to have shown me your face all this time!”

“It is not that I have not shown myself. You and I have never been separate. But your own negative actions and obscurations were too intense for you to be able to see me. Because your twelve years of practice have diminished them a little, you were able to see the bitch. Just now, because of your great compassion, your obscurations have been completely purified and you can see me with your own eyes. If you do not believe me, carry me on your shoulder and show me to everyone around!”

So Asanga placed Maitreya on his right shoulder and went to the market, where he asked everyone, “What do you see on my shoulder?”

Everyone replied there was nothing on his shoulder-all except one old woman whose perception was slightly less clouded by habitual tendencies. She said, “You are carrying the rotting corpse of a dog.”

Lord Maitreya then took Asanga to the Tusita heaven, where he gave him The Five Teachings of Maitreya and other instructions. When he came back to the realm of men, Asanga spread the doctrine of the Great Vehicle widely.

Since there is no practice like compassion to purify us of all our harmful past actions, and since it is compassion that never fails to make us develop the extraordinary bodhicitta, we should persevere in meditating upon it.

The image given for meditating on compassion is that of a mother with no arms, whose child is being swept away by a river. How unbearable the anguish of such a mother would be. Her love for her child is so intense, but as she cannot use her arms she cannot catch hold of him.

“What can I do now? What can I do?” she asks herself. Her only thought is to find some means of saving him. Her heart breaking, she runs along after him, weeping.

In exactly the same way, all beings of the three worlds are being carried away by the river of suffering to drown in the ocean of samsara, However unbearable the compassion we feel, we have no means of saving them from their suffering. Meditate on this, thinking, “What can I do now?” and call on your teacher and the Three Jewels from the very depth of your heart.

4. Meditation on sympathetic joy

Imagine someone of noble birth, strong, prosperous and powerful, someone who lives in the higher realms experiencing comfort, happiness and a long life, surrounded by many attendants and in great wealth. Without any feeling of jealousy or rivalry, make the wish that they might become even more glorious, enjoy still more of the prosperity of the higher realms, be free of all danger, and develop ever more intelligence and other perfect talents. Then tell yourself again and again how wonderful it would be if all other beings could live at such a level too.

Begin your meditation by thinking about a person who easily arouses positive feelings-like a relative, a close friend or someone you love who is successful, contented and at peace, and feel happy that this is so. When you have established that feeling of happiness, try to cultivate the same feeling toward those about whom you feel indifferent. Then focus on all kinds of enemies who have harmed you, and especially anybody of whom you feel jealous. Uproot the evil mentality that finds it unbearable that someone else should have such perfect plenty, and cultivate a particular feeling of delight for each kind of happiness that they might enjoy. Conclude by resting in the state without any conceptualization.

The meaning of sympathetic joy is to have a mind free of jealousy. You should therefore try to train your mind with all sorts of methods to prevent those harmful jealous thoughts from arising. Specifically, a Bodhisattva, who has given rise to bodhicitta for the benefit of all beings, should be trying to establish all those beings in the everlasting happiness of Buddhahood, and temporarily in the happiness of the realms of gods and men. So how could such a Bodhisattva ever be displeased instead when some beings, through the force of their own past actions, possess some distinction or wealth?

Once people have been corrupted by jealousy, they no longer see the good in others, and their own negative actions increase alarmingly.

When the glory and activity of Jetsun Milarepa were spreading, a certain professor of logic named Tarlo became jealous and started to attack him. In spite of every example of clairvoyance and miraculous power that the Jetsun showed him, Tarlo had no faith in him, and only reacted with wrong views and criticism. He was later reborn as a great demon.

There are many other examples of what can happen under the power of jealousy, like how the logician, Geshe Tsakpuwa, tried to poison Jetsun Mila.

Even if the Buddha himself were present in person, there would be nothing he could do to guide a jealous person. A mind tainted with jealousy cannot see anything good in others. Being unable to see anything good in them, it cannot give rise to even the faintest glimmer of faith. Without faith one can receive neither compassion nor blessings. Devadatta and Sunaksatra were the Buddha’s cousins. Both were tormented by jealousy and refused to have the slightest faith in him. Although they spent their entire lives in his company, he could not transform their minds at all.

Moreover, even when evil thoughts about others do not materialize as actual physical harm, they still create prodigious negative effects for the person who has the thought. There were once two famous geshes who were rivals. One day, one of them learned that the other had a mistress.

The geshe told his servant, “Prepare some good tea, because I have some interesting news.”

The servant made tea, and when he had served it he asked, “And what is the news?”

“They say,” replied the geshe, “that our rival has a mistress!”

When Kunpang Trakgyal heard this tale, it is said that his face darkened and he asked, “Which of the two geshes committed the worse action?”

Constantly dwelling on such feelings as jealousy and competitiveness neither furthers one’s own cause nor harms that of one’s rivals. It leads to a pointless accumulation of negativity. Give up vile attitudes of this kind. Always sincerely rejoice in the achievements and favourable circumstances of others, whether it be their social position, physique, wealth, learning or whatever else. Think over and over again how truly glad you are that they are such excellent people, so successful and fortunate. Think how wonderful it would be if they became even better off than they are now, and acquired all the strength, wealth, learning and good qualities that they could possibly ever get. Meditate on this from the depth of your heart.

The image given for boundless sympathetic joy is that of a mother camel finding her lost calf. Of all animals, camels are considered the most affectionate mothers. If a mother camel loses her calf her sorrow is correspondingly intense. But should she find it again her joy knows no bounds. That is the kind of sympathetic joy that you should try to develop.

The four boundless qualities cannot fail to cause us to develop genuine bodhicitta. It is therefore vital to cultivate them until they have truly taken root in us.

To make things as easy as possible to understand, we can summarize the four boundless qualities in the single phrase “a kind heart.” Just train yourself to have a kind heart always and in all situations.

One day, Lord Atisa’s hand was hurting, and so he laid it in Drom Tonpa’s lap and said, “You who are so kind-hearted, bless my hand!”*

(*It is customary to ask realized lamas to blow on a wound in order to cure it.)

Atisa always placed a unique emphasis on the importance of a kind heart, and rather than ask people, “How are you?,” he would say, “Has your heart been kind?”

Whenever he taught he would add, “Have a kind heart!”

It is the power of kind or unkind intentions that makes an action positive or negative, strong or weak. When the intention behind them is good, all physical or verbal actions are positive, as was illustrated by the story of the man who put the leather sole over the tsa-tsa. When the intention behind it is bad, any action, however positive it looks, will in fact be negative. So learn to have kind intentions all the time, no matter what the circumstances. It is said:

If the intention is good, the levels and paths are good.

If the intention is bad, the levels and paths are bad.*

Since everything depends on intentions,

Always make sure they are positive.

(*The ten levels and five paths of a Bodhisattva. Here the meaning seems to be progress on the path in general.)

How is it that the paths and levels are good if the intentions are good?

Once an old woman was crossing a wide river with her daughter, holding her hand, when both of them were swept away by the current.

The mother thought: “It’s not that important if I am carried away by the water, as long as my daughter is saved!”

At the same time, the young girl was thinking, “It doesn’t matter much if I get swept away, as long as my mother isn’t drowned!”

They both perished in the water, and as a result of those positive thoughts for each other, they were both reborn in the celestial realm of Brahma.

On another occasion, six monks and a messenger boarded a ferryboat to cross the river Jasako. The boat set off from the bank.

About a quarter of the way across, the boatman said, “We’re too heavy. If anybody knows how to swim, please jump in the water. If not, I’ll jump in myself and one of you can take the oars.”

None of them knew how to swim; but none of them knew how to row either.

So the messenger jumped out of the boat, crying, “It is better for me to die alone than for everybody to die!”

Immediately a rainbow appeared and a rain of flowers fell. Even though the messenger did not know how to swim, he was carried safely to the shore. He had never practised Dharma. This was the immediate benefit coming from a single good thought.

How is it that the paths and levels are bad if the thoughts are bad?

There was once a beggar who, as he was lying in the gateway of the royal palace, was thinking, “I wish that the king would have his head cut off and I could take his place!”

This thought was continually going round in his mind all night long. Towards morning he fell asleep and while he was sleeping the king drove out in his carriage. One of the wheels rolled over the beggar’s neck and cut off his head.

Unless you remember the purpose of your quest for Dharma with mindfulness and vigilance, and watch your mind all the time, violent feelings of attachment and hatred can easily lead to the accumulation of very serious negative effects. Although the old beggar’s wishes could never come true, the result of his thoughts materialized right away. Was it likely that the king, sleeping comfortably on his jewelled bed in the palace, would lose his head? Even if he were to be beheaded, would it not be more plausible that the crown prince would take over the kingdom? Even if somehow he did not, was there any chance that in spite of all the ministers, who were like tigers, leopards and bears, a scabrous old beggar would take over the throne? Unless you check yourself carefully, however, even such ludicrous negative thoughts as this can arise. So, as Geshe Shawopa says:

Do not rule over imaginary kingdoms of endlessly proliferating possibilities!

One day the Buddha and his monks were invited to receive alms at the home of a benefactor. There were also two beggars there, one a young ksatriya and the other a young brahmin. The brahmin went in to beg before the Buddha and the monks had been served, and received nothing. The ksatriya waited until everybody else had been served, and received plenty of the good food left over from their begging bowls.* That afternoon, on the road, the two of them spoke their thoughts to each other.

“If I were rich,” said the young ksatriya, “I would offer clothes and alms to the Buddha and his monks for the rest of my life. I would honour them by offering everything I had.”

“And if I were a powerful king,” said the young brahmin, “I’d have that shaven-headed bigot’s head cut off, and his whole band executed with him!”

(*From the earliest times, the tradition was that Buddhist monks offered the first part of what they received on their daily begging round to the Three Jewels, ate the middle part without discrimination, and gave the last part to the needy.)

The ksatriya went to another country and installed himself in the shadow of a great tree. As the shadows of the other trees moved, the shadow of this particular tree stayed still. Now, the king of that country had just died, and since he had no heir the people had decided that the most meritorious and powerful person in the land would be installed as their king. Going off in search of their new sovereign, they came upon the young ksatriya sleeping under his tree, still in the shade although midday had long since passed. They woke him up and made him king. Thereafter, he paid honour to the Buddha and his disciples as he had wished.

As for the young brahmin, the story goes that he lay down at a crossroads to rest and his head was cut off by the wheel of a passing wagon.

If you learn to always have only kind thoughts, all your wishes for this lifetime will come true. The benevolent gods will protect you and you will receive the blessings of all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Everything you do will be positive, and at the moment of death you will not suffer. In future lives you will always be reborn in celestial or human realms until finally you attain the level of perfect Buddhahood.

Do not just rush off, without examining your thoughts and feelings, and perform a great show of virtuous activities-prostrations, circumambulations, prayers, recitation of mantras and so on. Instead, it is important to check your attitude all the time and to cultivate a kind heart.

II. AROUSING BODHICITTA*

(*”Arousing bodhicitta” it means to give birth to, to produce, but also to make grow, to develop. The “mind of enlightenment,” has several levels of meaning. For the beginner, it is simply the intention to liberate all beings. However in a deeper sense, bodhicitta is a synonym of Buddha-nature, and of primal awareness (rigpa). At this level it is not something to be produced which was not there before, because it is the fundamental nature of our mind, which has always been with us and only has to be discovered and made manifest. We have chosen “arouse” to try to convey something of both aspects.)

1. Classification based on the three degrees of courage

1.1 THE COURAGE OF A KING

A king’s first priority is to overcome all his rivals, promote those who support him and proclaim himself sovereign. Only after that does his wish to take care of his subjects come into effect. Similarly, the wish first to attain Buddhahood for oneself and then to bring others to Buddhahood is called the king’s way of arousing bodhicitta.

1.2 THE COURAGE OF A BOATMAN

A boatman aims to arrive on the other shore together with all his passengers. Likewise, the wish to achieve Buddhahood for oneself and all beings at the same time is called the boatman’s way of arousing bodhicitta.

1.3 THE COURAGE OF A SHEPHERD

Shepherds drive their sheep in front of them, making sure that they find grass and water and are not attacked by wolves, jackals or other wild beasts. They themselves follow behind. In the same way, the attitude of those who wish to establish all beings of the three worlds in perfect Buddhahood before achieving it for themselves is called the shepherd’s way of arousing bodhicitta.

The king’s way, called “arousing bodhicitta with the great wish,” is the least courageous of the three. The boatman’s way, called “arousing bodhicitta with sacred wisdom,” is more courageous. It is said that Lord Maitreya aroused bodhicitta in this way. The shepherd’s way, called “the arousing of bodhicitta beyond compare,” is the most courageous of all. It is said to be the way Lord Manjusri aroused bodhicitta.

2. Classification according to the Bodhisattva levels

On the paths of accumulating and joining, arousing bodhicitta is called “arousing bodhicitta by practising with aspiration.” From the first to the seventh Bodhisattva level, it is called “arousing bodhicitta through excellent and perfectly pure intention. ” On the three pure levels, it is called “arousing fully matured bodhicitta,” and at the level of Buddhahood, “arousing bodhicitta free from all obscurations.”

3. Classification according to the nature of bodhicitta

There are two types of bodhicitta: relative and absolute.

3.1 RELATIVE BODHICITTA

Relative bodhicitta has two aspects: intention and application.

3.1.1 Intention

In The Way of the Bodhisattva, Santideva says of these two aspects of bodhicitta:

Wishing to depart and setting out upon the road,

This is how the difference is conceived.

The wise and learned thus should understand

This difference, which is ordered and progressive.

Take the example of a journey to Lhasa. The first step is the intention, “I am going to go to Lhasa.” The corresponding initial thought, “I am going to do whatever will ensure that all beings attain the state of total Buddhahood,” is the intention aspect of arousing bodhicitta.*

(*”To promise to attain the fruit.”)

3.1.2 Application

You then prepare the necessary supplies and horses, set out on the road and actually travel to Lhasa. Similarly, you decide to practise generosity, preserve discipline, cultivate tolerance, apply diligence, remain in meditative absorption, and train your mind in discriminating wisdom in order to establish all beings on the level of perfect Buddhahood, and you actually put this path of the six transcendent perfections into practice. This corresponds to the actual journey, and is the application aspect of bodhicitta.*

(*The bodhicitta of application is the will to practise the six transcendent perfections, which are the cause or the means of attaining the fruit.)

3.2 ABSOLUTE BODHICITTA

Both the intention and application aspects are relative bodhicitta.* Through training for a long time in relative bodhicitta on the paths of accumulating and joining, you come at last to the path of seeing, where you have the real experience of thusness, the natural state of all things. This is the wisdom beyond all elaboration, the truth of emptiness. At that time you arouse absolute bodhicitta.**

(*Relative bodhicitta is produced with the support of our thoughts.)

(**Absolute bodhicitta is wisdom in which the movements of thought have dissolved.)

4. Taking the vow of bodhicitta

True absolute bodhicitta is attained by the power of meditation and does not depend on rituals. To generate relative bodhicitta, however, as beginners we need some procedure to follow, a ritual through which we can take the vow in the presence of a spiritual teacher. We then need to constantly renew that vow, in the same way, over and over again, so that the bodhicitta we have aroused does not decline but becomes more and more powerful.

Visualize all the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and other deities in the sky before you, as for the refuge practice. Take them as witnesses of your generating bodhicitta and think like this:

“Of all the countless living creatures throughout the vast reaches of the universe, there is not one who has not been my parent in the course of our succession of lives without beginning. I can be certain that, as my parents, they have all looked after me with every possible tenderness, given me the very best of their own food and clothing and nurtured me with all their love, just as my present parents have done. Now all these kind parents are foundering in the waves of samsara’s great ocean of suffering. They have been plunged into the deepest darkness of confusion. They have no idea of the true path to be practised, nor of the false path to be avoided. They have no authentic spiritual friend to guide them. They have no refuge or protection, no leader or companion, no hope and nobody to turn to, as lost as a blind man wandering friendless in the middle of a deserted plain. My old mothers, how could I ever liberate myself alone and leave you all behind here in samsara? For the sake of all beings, I shall awaken the sublime bodhicitta. Learning to emulate the mighty deeds of the Bodhisattvas of the past, I shall make whatever efforts are necessary, till there is not one being left in samsara!”

With this attitude, recite the following verse as many times as possible:

Ho! Led astray by myriad appearances like reflections of the moon in water,

Beings wander in the endless chain of samsara;

To bring them rest in the radiant space of awareness,

With the four boundless qualities I arouse bodhicitta.*

(*The moon’s reflection in water appears vividly but has no true, independent existence. The same is true of what we perceive through the senses, since phenomena are empty of any objective essence. However, we are led astray by the belief that those appearances are objectively real. It is this fundamental confusion which is the basis for the negative emotions which make us wander in samsara.)

At the close of the session visualize that, by the power of your yearning devotion towards the deities of the field of merit, the whole assembly melts into light, starting from the outside, and finally dissolves into the teacher, union of all three refuges, in the centre. The teacher in turn melts into light and dissolves into you, causing the absolute bodhicitta present in the mind of the refuge deities to arise clearly in your own mind. Make this wishing prayer:

May bodhicitta, precious and sublime,

Arise where it has not yet come to be;

And where it has arisen may it never fail

But grow and flourish ever more and more.

Then dedicate the merit with the lines:

Emulating the hero Manjusri,

Samantabhadra and all those with knowledge,

I too make a perfect dedication

Of all actions that are positive.

This arousing of bodhicitta is the quintessence of the eighty-four thousand methods taught by the Conqueror. It is the instruction to have which is enough by itself, but to lack which renders anything else futile. It is a panacea, the medicine for a hundred ills. All other Dharma paths, such as the two accumulations, the purification of defilements, meditation on deities and recitation of mantras, are simply methods to make this wish-granting gem, bodhicitta, take birth in the mind. Without bodhicitta, none of them can lead you to the level of perfect Buddhahood on their own.* But once bodhicitta has been aroused in you, whatever Dharma practices you do will lead to the attainment of perfect Buddhahood. Learn always to use whatever means you can to make even the slightest spark of bodhicitta arise in you.**

(*The reason why bodhicitta is so fundamental to the path of enlightenment is because at the absolute level it is the Buddha-nature itself, inherent in all beings, which naturally has limitless love and compassion. The process of relative bodhicitta serves to make that nature manifest. Of these two aspects: “The first is the deep cause of attaining Buddhahood, and the second is the circumstantial cause.”)

(**One should first try to arouse bodhicitta for the merest instant, then for two, then three and so on.)

The teacher who gives you the pith instructions on arousing bodhicitta is setting you on the path of the Great Vehicle, so his kindness is greater than that of teachers who give you any other instructions. When Atisa mentioned the names of his teachers, he used to join his hands before his heart. But when he spoke of Lord Suvarnadvipa, he would join his hands above his head and his eyes would fill with tears. His disciples asked him why he made such a distinction.

“Is there really a difference in the spiritual qualities or kindness of these masters?” they asked.

“All my teachers were truly accomplished beings,” Atisa replied, “and in this their qualities are identical. But there is some difference in their kindness. The little bit of bodhicitta that I have comes from the kindness of Lord Suvarnadvipa. That is why I feel the greatest gratitude toward him.”

It is said that the most important thing about bodhicitta is not arousing it, but rather that it has actually arisen. The love and compassion of bodhicitta must really be alive in us. To recite the formula many hundreds of thousands of times without taking the meaning to heart, therefore, is utterly pointless. To take the bodhicitta vow in the presence of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, and then not to keep it, would just be to swindle them. There is no worse fault than that. So do not cheat sentient beings either-try to cultivate bodhicitta all the time.

III. TRAINING IN THE BODHICITTA PRECEPTS

For the bodhicitta of intention, the training has three stages: considering others as equal to oneself, exchanging oneself and others and taking others as more important than oneself. For the bodhicitta of application, the training consists of practising the six transcendent perfections.

1. Training in the precepts of the bodhicitta of aspiration

1.1 CONSIDERING OTHERS AS EQUAL TO ONESELF

The reason we have been wandering in samsara’s ocean of suffering from time without beginning is that we believe in an “I” where there is no I, in a “self” where there is no self, and that we make that self the sole object of our affection. Instead, reflect as follows.

We want to be happy constantly and never to have any kind of suffering. The moment anything unpleasant happens to us we find it unbearable. Even a pinprick or the tiny burn of a spark makes us cry out in pain-we just cannot stand it. If a little louse should bite us on the back we fly into a rage. We catch that louse, put it on one of our thumbnails and crush it hard with the other, and long after we have already killed it we go on and on grinding our nails together in anger. Most people these days see no harm in killing a louse. But since it is invariably done out of anger, it is a sure cause for rebirth in the Rounding-Up and Crushing Hell. We should be ashamed to find such small discomforts so hard to bear and to react in a way that causes so much pain to another being.

Just like us, all beings of the three worlds want to be happy and to escape any kind of suffering, too. But although they want to be happy, they have no idea that happiness comes only from practising the ten positive actions. Although they do not want to suffer, they devote all their efforts to the ten harmful actions which bring about suffering. What they wish for and their attempts to attain it are therefore completely at odds, and they suffer all the time. Of all those beings, there is not a single one who has not, at some moment throughout time without beginning, been a parent to us. Now that we have been accepted as disciples by an authentic spiritual teacher, now that we have taken up the true Dharma and can distinguish what is profitable from what is detrimental, we ought to be caring lovingly for all our old mothers so enslaved by their own confusion, and should stop seeing any difference between them and ourselves. Putting up with their ingratitude and prejudices, we should meditate on the absence of any difference between friends and enemies.

Keeping all this in mind, meditate on it over and over again.

Whatever good or useful things you want for yourself, others want them just as much. So just as you work hard at bringing about your own happiness and comfort, always work hard for others’ happiness and comfort, too. Just as you would try to avoid even the slightest suffering for yourself, strive too to prevent others having to suffer even the slightest harm. Just as you would feel pleased about your own well-being and prosperity, rejoice from your heart when others are well and prosperous, too. In short, seeing no distinction between yourself and all living creatures of the three worlds, make it your sole mission to find ways of making everyone of them happy, now and for all time.

When Trungpa Sinachen asked him for a complete instruction in a single sentence, Padampa Sangye replied, “Whatever you want, others all want as much; so act on that!”

Completely eradicate all those wrong attitudes based on attachment and aversion which make you reject others and care only about yourself, and think of yourself and others as being entirely equal.

1.2 EXCHANGING ONESELF AND OTHERS

Look at a person actually suffering from sickness, hunger, thirst or some other affliction. Or, if that is not possible, imagine that such a person is in front of you. As you breathe out, imagine that you are giving that person all your happiness and the best of everything you have, your body, your wealth and your sources of merit, just as if you were taking off your own clothes and dressing the other person in them. Then, as you breathe in, imagine that you are taking into yourself all the other person’s sufferings and that, as a result, he or she becomes happy and free from every affliction. Start this meditation on giving happiness and taking suffering with one individual, and then gradually extend it to include all living creatures.

Whenever anything undesirable or painful happens to you, generate heartfelt, overwhelming pity for all the many beings in the three worlds of samsara who are now undergoing such pain as yours. Make the strong wish that all their suffering may ripen in you instead, and that they may all be freed from suffering and be happy. Whenever you are happy or feel good, generate the wish that your happiness might extend to bring happiness to all beings.

This bodhicitta practice of exchanging oneself and others is the ultimate and unfailing quintessential meditation for all those who have set out on the path of the Mahayana teachings. If you really experience that exchange happening even once, it will purify the negative actions and obscurations of many kalpas and create an immense accumulation of merit and wisdom. It will save you from the lower realms and from any rebirths that might lead to them.

In a previous life, the Buddha was born in a hell where the inhabitants were forced to pull wagons. He was harnessed to a wagon with another person called Kamarupa, but the two of them were too weak to get their vehicle to move. The guards goaded them on and beat them with red-hot weapons, causing them incredible suffering.

The future Buddha thought, “Even with two of us together we can’t get the wagon to move, and each of us is suffering as much as the other. I’ll pull it and suffer alone, so that Kamarupa can be relieved.”

He said to the guards, “Put his harness over my shoulders, I’m going to pull the cart on my own.”

But the guards just got angry. “Who can do anything to prevent others from experiencing the effects of their own actions?” they said, and beat him about the head with their clubs

Because of this good thought, however, the Buddha immediately left that life in hell and was reborn in a celestial realm. It is said that this was how he first began to benefit others.

Another story tells how the Buddha, in a previous rebirth as the “daughter” of the sea-captain Vallabha, was once again freed from the lower realms as soon as he really experienced this exchanging of himself with others. There was once a householder called Vallabha, all of whose sons had died. So, when another son was born, he decided to name him Daughter in the hope that this would keep him alive. Vallabha then went to sea in search of precious gems, but his ship sank and he perished.

When the son grew up, he asked his mother what his father’s caste occupation had been. His mother, fearing that were she to tell him the truth he too might go to sea, told him that his father had belonged to the caste of grain merchants. So Daughter became a grain merchant and looked after his mother with the four coins of one karsa he earned each day. But soon the other grain merchants told him that he was not a member of their caste and that, consequently, it was not proper for him to practise their trade. He was forced to stop.

He went back to his mother and questioned her again. This time she told him that his father had been an incense seller. He started selling incense, and with the eight karsa he earned each day, he took care of his mother.

But Daughter was stopped once again, and this time his mother told him that his father had sold clothes. He set up as a clothing merchant, and was soon able to give his mother sixteen karsa a day. But yet again he was forced out of business by the other clothing merchants.

When he was told that he was of the jewellers’ caste, he started to sell jewels and brought home thirty-two karsa a day to give to his mother. It was then that the other jewellers told him that he belonged to the caste of those who brought back jewels from ocean voyages and that this was the work he was born to do.

When he got home that day, he said to his mother, “I belong to the caste of those who search for jewels. So I’m going to sail across the great ocean to carryon my own trade!”

“It is true that you are of the jewel hunters’ caste,” said she, “but your father and all your ancestors have died at sea in their quest for jewels. If you go you’ll die too. Please don’t go! Stay at home and trade here.”

But Daughter could not obey her. He prepared everything he needed for his journey. As he was setting out, his mother, unable to let him go, caught hold of the hem of his garment and wept. He was furious.

Crying, “Your tears will bring me bad luck on the journey across the ocean!” he kicked her in the head and left.

During the voyage, his ship was wrecked and almost the entire crew was drowned, but Daughter held fast to a plank and was washed ashore on an island. He came to a town called Joy. In a beautiful house made of precious metals and jewels, four beautiful goddesses piled up silken cushions for him to sit on and offered him the three white and three sweet foods.

As he prepared to leave, they warned him, “Do not travel toward the south. Great misfortune will befall you if you do!” But Daughter did not listen and took to the road.

He came to a town called Joyous, even more beautiful than the one before. Here eight beautiful women placed themselves at his service. As before, they warned him of great misfortune threatening him if he went towards the south, but he took no notice and set off yet again.