Offering the Mandala to Accumulate Merit and Wisdom

From Words of My Perfect Teacher:

Chapter Four

You know the relative to be a lie, yet still you practise the two accumulations.

You realize that in the absolute there is nothing to be meditated on, yet still you practise meditation.

You see relative and absolute as one, yet still you diligently practise.

Peerless Teacher, at your feet I bow.

I. THE NEED FOR THE TWO ACCUMULATIONS

It is impossible to attain the twofold purity* of Buddhahood or to realize fully the truth of emptiness without completing the two accumulations of merit and wisdom.

(*The twofold purity is to possess the purity of the Buddha nature in the first place, and then the purity of having actualized it and achieved Buddhahood. “According to the teachings of the Nyingma tradition, the primordially pure nature which is Buddhahood and the qualities of the three kayas already dwell within us in their entirety, and we do not need to seek them elsewhere. But if we do not use the two accumulations as auxiliary factors, these qualities will not become manifest. It is like the sun: although its rays illuminate the sky by themselves, it is still necessary for the wind to drive away the clouds which hide it.)

As it says in the sutras:

Until one has completed the two sacred accumulations,

One will never realize sacred emptiness.

And:

Innate absolute wisdom can only come

As the mark of having accumulated merit and purified obscurations.

And through the blessings of a realized teacher.

Know that to rely on any other means is foolish.

Even those who have truly realized emptiness need to maintain their progress along the path until they attain perfect Buddhahood, so they still need to make efforts to accumulate merit and wisdom. Tilopa, the Lord of Yogis, said to Naropa:

Naropa, my son, until you realize

That all these appearances which arise interdependently

In reality have never arisen, never part

From the two wheels of your chariot, the two accumulations.

The great yogi Virupa says in his Dohas:

You may have the great confidence of not hoping for relative

Buddhahood,* But never give up the great accumulation of merit; endeavour as much as you can.

And the peerless Dagpo Rinpoche says:

Even when your realization transcends the very notions of there being anything to accumulate or purify, continue still to accumulate even the smallest amounts of merit.

The Conqueror, in his great compassion and with all his skill in means, taught innumerable methods by which the two accumulations can be performed. The best of all these methods is the offering of the mandala, A tantra says:

To offer to the Buddhas in all Buddhafields

The entire cosmos of a billion worlds,

Replete with everything that could be desired,

Will perfect the primal wisdom of the Buddhas.*

(*Meaning that the accumulation of merit through this practice will allow the perfect wisdom of one’s Buddha nature to manifest.)

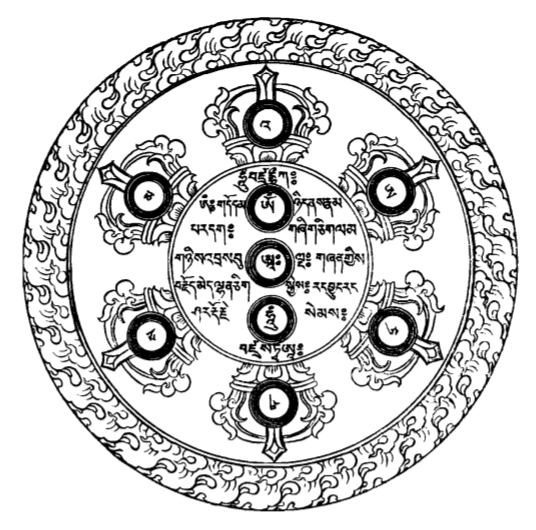

In this tradition, when making such an offering, we use two separate mandalas: the accomplishment mandala and the offering mandala.

The material out of which the mandala should be made depends on our means. The best kind of mandala base would be made of precious substances such as gold and silver. A medium quality one would be made of bell-metal or some other fine material. At worst, you could even use a smooth flat stone or a piece of wood.

The offering piles placed on the mandala base would ideally consist of precious stones: turquoises, coral, sapphires, pearls and the like. Second best would be medicinal fruits such as arura and kyurura. Ordinarily they would consist of grains such as barley, wheat, rice or pulses, but at the very worst you could also just use pebbles, gravel, sand and so on, simply as a support for your visualization.

Whatever material your mandala base is made of, clean it with great care.

II. THE ACCOMPLISHMENT MANDALA*

(*The directions that follow are sometimes quite technical and are intended to complement an oral explanation, normally accompanied by a demonstration.)

Begin by arranging five piles on the accomplishment mandala.*

(*We make offerings in the presence of the accomplishment mandala, which is used rather as one might use a statue of the Buddha. It symbolizes the perfect Buddhafield of the five Buddhas which represent the five wisdoms. As it is these five wisdoms which we wish to accomplish, this mandala is called the accomplishment mandala.)

Put one small pile in the centre to represent the Buddha Vairocana surrounded by the deities of the Buddha Family. Put another one in the eastern direction-meaning towards yourselfl04-to represent the Buddha Vajra Aksobhya surrounded by the deities of the Vajra Family. Then one in the south for the Buddha Ratnasambhava surrounded by the deities of the Jewel Family, one in the west for the Buddha Amitabha surrounded by the deities of the Lotus Family, and one in the north for the Buddha Amoghasiddhi surrounded by the deities of the Action Family.

Another possibility is to visualize the field of merit as in the refuge practice. The central pile would then represent the Great Master of Oddiyana, inseparable from your own root teacher, with all the teachers of the Great Perfection lineage above him, arranged in order, one above the other. The front pile would represent the Buddha Sakyamuni, surrounded by the thousand and two Buddhas of this Good Kalpa. The pile on the right would represent his eight great Close Sons surrounded by the noble sangha of Bodhisattvas, and the pile on the left would represent the Two Principal Sravakas, surrounded by the noble sangha of Sravakas and Pratyekabuddhas. The pile at the back would be the Jewel of the Dharma, in the form of stacked-up books encased in a lattice of light rays.

Whichever is the case, place this accomplishment mandala on your altar or another suitable support. If you have them, surround it with the five offerings,* and place it in front of representations of the Buddha’s body, speech and mind. If this is not feasible, it is also possible to dispense with the accomplishment mandala altogether, and simply to visualize the field of merit.

(*The five offerings are flowers, incense, lamps, perfume and food.)

III. THE OFFERING MANDALA

Holding the offering mandala base with your left hand, wipe it for a longtime with the underside of your right wrist while you recite the Seven Branches and other prayers, without ever being distracted from what you are visualizing.

This wiping of the base is not only to clean away any dirt on the mandala base. It is also a way of using the effort we put into this task to rid ourselves of the two obscurations which veil our minds. The story goes that the great Kadampas of old cleaned their mandalas with the undersides of their wrists until the skin was worn through and sores started to form. They still carried on, using the edge of their wrists. When sores formed there, they used the back of their wrists instead. So when you clean the mandala base, do not use a woollen or cotton cloth but only your wrist, like the great Kadampas of the past.

As you arrange the offering piles on the base, follow the prayer known as The Thirty-seven Element Mandala, which was composed by Chogyal Pakpa, the Protector of Beings of the Sakya school. This method is easy to practice, and has therefore been adopted by all traditions both old and new without distinction. Here we start by offering the mandala in this way because that is our tradition too.

Both the old and the new traditions have several other methods, each according to its own customs. Indeed, each spiritual treasure of the Nyingma tradition has its own mandala offering. In this particular tradition of ours there are several detailed offering prayers for the mandala of the three kayas taught by the Omniscient Longchenpa in the various Heart-essences.* Any of these can be chosen.

(*The Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse is one of a number of Heart-essence teachings. The most important of these are the Heart-essence of the Dakini and the Heart-essence of Vimalamitra, transmitted through Yeshe Tsogyal and Vimalamitra respectively. Both these teachings have come down through the lineage of Longchenpa.)

1. The thirty-seven element mandala offering

Start by saying the mantra:

Om Vajra Bhumi Ah Hum,

At the same time holding the mandala in your left hand and with your right sprinkling it with perfumed water containing bajung.* Then, with your right thumb and ring finger, take a small pinch of grain. Saying:

Om Vajra Rekhe Ah Hum,

(*A ritual preparation made from five different substances collected from a cow.)

Circle your hand clockwise on the mandala base and then place the pinch of grains in the middle. If you have a ready-made “fence of iron mountains,”* now is the time to place it on the mandala, Reciting:

Mount Meru, King of Mountains,

(*A ready made “iron fence” is a ring, usually of metal which one uses to contain the first level of offerings of the mandala. It represents the ring of mountains surrounding the world. In such a case a second ring contains the offerings of the eight goddesses and a third the sun, moon, etc. The ornament for the summit mentioned later is simply a jewel-shaped ornament which one puts on top at the end. These accessories are additions to enhance the offering, which is nonetheless perfectly authentic without them.)

Place a larger pile in the centre. To layout the four continents, recite:

To the East, Puruauideba …,

And place a small pile in the east, which can be either on the side towards you or on the opposite side, facing those to whom you are making the offering.* Then put three piles for the other continents, going round in a clockwise direction from the east.

(*If you arrange the mandala so that the East is towards you, you should turn the completed mandala round to face the mandala of accomplishment at the end, when you recite, “I offer this mandala …”)

For the subcontinents, Deha, Videha and so on, place a pile on either side of each continent in turn.

Next, place the Precious Mountain in the east, the Wish-fulfilling Tree in the south, the Inexhaustibly Bountiful Cow in the west and the Spontaneous Harvest in the north.

Then come the Seven Attributes of Royalty plus the Vase of Great Treasure, which are placed one after another in the four cardinal and four intermediate directions.

Next, place the four outer goddesses in each of the four cardinal directions, beginning with the Lady of Beauty; and the four inner goddesses in the four intermediate directions, beginning with the Lady of Flowers.

Place the Sun in the east and the Moon in the west. Place the Precious Umbrella in the south and the Banner Victorious in All Directions in the north.

As you recite:

All the wealth of gods and men, leaving out nothing …

Pile more grains on top of the rest so that no space is left unfilled. If you have an ornament for the summit, place it on top now. Recite:

I offer this mandala to all the glorious and sublime root and lineage teachers and to all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

At this point some people add the words, “… pleasant and complete in all its parts, lacking nothing,” but according to my teacher, that is an addition not found in the original text.

As to what should be visualized for each of these points, my teacher did not say any more than this when he gave the teaching, so I shall write nothing more here myself. However, those who wish to know the details should consult the Detailed Commentary on the Condensed Meaning, as suggested in the basic explanatory text for these preliminary practices.*

(*The basic explanatory text for these preliminary practices is the Explanation of the Preliminary Practice of the Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse, written by Jigme Lingpa. Each element of the mandala has several levels of meaning, corresponding to different levels of practice.)

2. The mandala offering of the three kayas according to this text

2.1 THE ORDINARY MANPALA* OF THE NIRMANAKAYA

(*Though more ordinary than those which follow, this is nonetheless an offering of an ideal universe, as perceived in the pure vision of highly evolved beings rather than the everyday experience of a universe full of suffering perceived by ordinary deluded perception.)

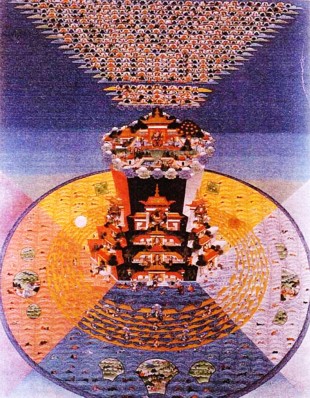

The four continents mentioned above in the arrangement of the piles of offering substances, with Mount Meru in the centre and the realms of the Brahma heavens above it, make up one world. One thousand of those worlds make up what is called “a first-order universe of one thousand worlds.” Taking such a universe consisting of a thousand worlds, each with four continents, and multiplying it a thousand times, we get what is called “a second-order intermediate universe of one thousand times one thousand worlds,” or a universe of a million worlds. Taking such a millionfold universe and again multiplying that a thousand times gives us “a third-order great universal system of one thousand million worlds,” or a cosmos of a billion universes. A universe of this order, made up of one thousand million worlds of four continents each, is the dominion of a single manifest Buddha – Sakyamuni, for example, whose Buddhafield is called The Universe of Endurance.

(*In this universe the emotions are so strong that beings are never separate from them.)

Imagine, throughout all of these innumerable and inconceivable worlds, all the most exquisite treasures to be found in human or celestial realms, such as the seven attributes of royalty and so on, whether owned by anyone or not. To all that add your own body, your wealth, life, good fortune, power and strength, as well as all the sources of merit that you have accumulated throughout all time and will accumulate in future, together with everything that could ever bring pleasure and happiness. Pile up everything that is best and most desirable and, without even as much as a sesame seed of desire or attachment, offer it all to your teacher and the deities of the nirmanakaya, complete and lacking nothing. This is the offering of the ordinary mandala of the nirmanakaya.

2.2 THE EXTRAORDINARY MANDALA OF THE SAMBHOGAKAYA

Above all that, create in your imagination an infinity of heavenly realms and inconceivable palaces in the five great Buddhafields,* all graced by the Lady of Beauty and the other goddesses offering the delights of the senses, multiplied infinitely. Offer all of this to your teacher and the deities of the sambhogakaya, This is the offering of the extraordinary mandala of the sambhogakaya.

(*The five great arrangements. These are the Buddhafields of the Buddhas of the five families.)

2.3 THE SPECIAL MANDALA OF THE DHARMAKAYA

Upon the mandala base representing unborn absolute space, place piles representing the four visions and whatever thoughts arise. Offer them to your teacher and the deities of the dharmakāya. This is the offering of the special mandala of the dharmakāya.

For this mandala offering of the three kayas, maintain a clear idea of all these instructions for the practice and repeat with devotion the prayer beginning:

Om Ah Hum. The cosmos of a billion universes, the field of one thousand million worlds …

While you are counting the number of offerings you make, hold the mandala base in your left hand, leaving the offerings you made the first time still on it, and for each recitation of the text add one pile with your right hand. Practise with perseverance, holding up the mandala base until your arms ache so much that they can no longer keep it up. “To bear hardships and persevere courageously for the sake of the Dharma” means more than just going without food.* It means always being determined to complete any practice that is difficult to do, whatever the circumstances. Practise like this, and in doing so you will acquire a tremendous amount of merit through your patience and effort.

(*Like Milarepa, who lived in remote places in the mountains where there was no-one to bring him food, and subsisted on a diet of nettles.)

When you can truly hold the mandala no longer, put it down on the table in front of you and continue piling on the heaps of offering and counting the number of times. When you take a break, for tea for instance, collect up everything you have offered, and when you start again begin with the thirty-seven element mandala before continuing as before.

Be sure to make at least one hundred thousand mandala offerings in this way. If you cannot manage that number using the detailed mandala of the three kayas, it is acceptable instead to recite the verse beginning:

The ground is purified with perfumed water …

While offering the seven-element mandala.*

(*In this simpler mandala offering one uses only seven piles of grain, to represent Mount Meru, the four continents, the sun and the moon.)

Whatever form the offering takes, it is important-as with every practice you do-to apply the three supreme methods. Start by arousing bodhicitta, do the practice itself without any concepts, and seal the practice perfectly at the end with the dedication of merit.

If it is barley, wheat, or another grain that you are using for the mandala offering, as long as you can afford the expense, always offer fresh grain and do not use the same grain twice. What has already been offered you can give to the birds, distribute to beggars, or pile up in front of a representation of the Three Jewels. But never think of it as your own or use it for yourself. Should you lack the resources to renew the offerings every time, do so as often as your means allow. If you are very poor, you can use the same measure of grain over and over again.

However often you change the grain, clean it before offering it by picking out all foreign bodies, dust, chaff, straw, bird droppings and the like, and saturate it with saffron or other scented water.

Although the teachings do permit the offering of earth and stones, this is for the benefit of those so poor that they have no possessions at all, or for those with such superior faculties that their minds can create, on a single speck of dust, Buddhafields as numerous as all the particles of earth in the whole world. You may actually have what is necessary but, unable to let go and generously offer it, you may claim with all sorts of considered and highly plausible reasons-and even convince yourself-that you are making offerings using mantras and visualization. But you will only be fooling yourself.

Moreover, all the tantras and pith instructions speak of “clean offerings, cleanly prepared” or “these cleanly prepared objects of offering.” They never recommend “dirty offerings, dirtily prepared.” So never offer left overs or food that is contaminated with stinginess or dirty. Do not take the best of the barley for your own consumption and leave the rest for offerings or to make tsampa for tormas. The ancient Kadampas used to say:

To keep the best for yourself and offer mouldy cheese and withered vegetables to the Three Jewels will not do.

Do not make tormas or lamp-offerings with rancid or rotten ingredients, keeping for your own use whatever is not spoiled. That sort of conduct will deplete your merit.

When making shelze* or tormas, prepare the dough with the consistency that you yourself would like. It is wrong to add a lot of water to the dough just because it makes it easier to work.

(*An honorific term for food. In this case an offering of food represented by a type of torma which bears this name.)

Atisa used to say: “These Tibetans will never be rich, they make their torma-dough too thin!”

He also said: “In Tibet, just to offer water is enough to accumulate merit. In India it is too hot, and the water is never as pure as here in Tibet.”

As a way of accumulating merit, offering clean water is extremely effective if you can do it diligently. Clean the seven offering bowls or other recipients and lay them out side by side, not too close together and not too far apart. They should all be straight, with none of them out of line. The water should be clear with no grains, hair, dust or insects floating in it. The bowls should be filled with care, full but not quite to the brim, without spilling any water on the offering table. This is the way to make beautiful and pleasing water offerings.

The Prayer of Good Actions speaks of offerings “arranged perfectly, distinctively and sublimely …” Whatever form of offering you make, if you make it beautiful and pleasing, even in the way it is set out, the respect you show to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in so doing will bring a vast amount of merit. So make the effort to arrange your offerings well.

If you lack resources or are otherwise unable to make offerings, there is nothing wrong with offering even something dirty or unpleasant, as long as your intention is perfectly pure. The Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have no concepts of clean or dirty. There are examples of such offering in stories, like the one about a poor woman known as Town Scavenger offering the Buddha a butter lamp. And there is the story of the leper woman who offered to Mahakasyapa a bowl of rice-gruel she had received on her begging round. As she was offering it to Mahakasyapa, a fly fell in. When she tried to fish out the fly her finger fell in too. Mahakasyapa drank it anyway in order to fulfil her good intention, and as her offering had provided him with a whole day’s food, the leper woman was filled with joy. She was reborn in the Heaven of the Thirty-three.

In short, when you offer the mandala, whatever you use should be clean, it should be offered in a pleasing way, and your intention should be utterly pure.

At no stage of the path should you stop trying to perform practices for accumulating merit, such as the mandala offering. As the tantras say:

Without any merit there can be no accomplishment;

One cannot make oil by pressing sand.

To hope for any accomplishments without accumulating merit is like trying to get vegetable oil by pressing sand from a river bank. No matter how many millions of sand grains you press, you will never get the tiniest drop of oil. But to seek accomplishments by accumulating merit is like trying to get oil by pressing sesame seeds. The more seeds you press, the more oil you will get. Even a single seed crushed on your fingernail will make the whole nail oily. There is another similar saying:

Hoping for accomplishments without accumulating merit is like trying to make butter by churning water.

Seeking accomplishments after accumulating merit is like making butter by churning milk.

There is no doubt that attaining the ultimate goal, supreme accomplishment, is also the fruit of completing the two accumulations. We have already discussed the impossibility of attaining the twofold purity of Buddhahood without having completed the accumulations of merit and wisdom. Lord Nagarjuna says:

By these positive actions may all beings

Complete the accumulations of merit and wisdom

And attain the two supreme kayas

Which come from merit and wisdom.

By completing the accumulation of merit, which involves concepts,* you attain the supreme rupakaya. By completing the accumulation of wisdom, which is beyond concepts, you attain the supreme dharmakaya,

(*Concepts of subject, object and action.)

The temporary achievements of ordinary life are also made possible by accumulated merit. Without any merit, all our efforts, however great, will be in vain. Some people, for example, without ever having to make the slightest effort, are never short of food, money or possessions in the present because of the stock of merit they have accumulated in the past. Other people spend their whole lives rushing hither and thither trying to get rich through trade, farming and so on. But it does them not even the tiniest bit of good, and they end up dying of hunger. This is something that everyone can see for themselves.

The same applies even to propitiating wealth deities, Dharma protectors and so on in the hopes of obtaining a corresponding supernatural accomplishment. Such deities can grant us nothing unless we can draw on the fruit of our own past generosity.

There was once a hermit who had nothing to live on, so he started doing the practice of Damchen.* He became so expert in the practice that he could converse with the protector as if with another person, but he still achieved no accomplishment.

(*Damchen Dorje Lekpa, Skt, Vajrasadhu, one of the principal Dharma protectors.)

Damchen told him: “Even the faintest effects of any past generosity are lacking in you, so I cannot bring you any accomplishment.”

One day the hermit lined up with some beggars and was given a full bowl of soup. When he got home, Damchen appeared and said to him; “Today I granted you some accomplishment. Did you notice?”

“But all the beggars got a bowl of soup, not only me,” said the hermit. “I don’t see how there was any accomplishment coming from you.”

“When you got your soup,” Damchen said, “a big lump of fat fell into your bowl, didn’t it? That was the accomplishment from me!”

Poverty cannot be overcome through wealth practices and the like without some accumulation of merit in past lives. If such beings as the worldly gods of fortune were really able to bestow the supernatural accomplishment of wealth, the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, whose power and ability to perform miracles are hundreds and thousands of times greater, and who devote themselves entirely to helping beings without even being asked, would certainly rain down such an abundance of wealth on this world that all poverty would be eliminated in an instant. But this has not happened.

Since whatever we have is only the result of the merit we have accumulated in the past, one spark of merit is worth more than a mountain of effort. These days when people see the slightest wealth or power in this barbaric land of ours, they are all amazed and exclaim, “My, my! How is it possible?” In fact this sort of thing does not require much in the way of accumulated merit at all. The effect of making an offering, when the intention of the one who offers and the object to which the offering is made are both pure, is exemplified by the tale of Mandhatri, By offering seven beans he won sovereignty over everything up to the Heaven of the Thirty three. Then there is the case of King Prasenajit, whose power was the result of offering a dish of hot food with no salt.

When Arisa came to Tibet, the country was much richer and bigger than it is today. And yet he said, “Tibet is really a kingdom of preta cities. Here I see no-one reaping the fruit of having offered even a single measure of barley to a pure object!”

If people really find everyday possessions or a little power so wonderful and amazing, it is a sign, first of all, of how small-minded they are; secondly, of how strongly attached they are to ordinary appearances; and thirdly, of their failure to understand properly the proliferating effects of actions, as illustrated earlier by the seed of the asota tree – or of the fact that they do not believe it, even if they do understand.

But anyone with sincere and heartfelt renunciation will know that of all the apparent perfections to be found in this world – even to be as rich as a naga, to have a position as high as the sky, to be as powerful as thunderbolt or as pretty as a rainbow-none of this has the tiniest speck of permanence, stability or substance. Such things should only arouse disgust, like a plate of greasy food offered to a person with jaundice.

A disciple of the peerless Dagpo Rinpoche once asked him: “In this degenerate age it is difficult to find food clothing and other necessities in order to practise the true Dharma. So what should I do? Should I try to propitiate the wealth deities a little, or learn a good method to extract essences,* or resign myself to certain death?”

(*Extracting the essences, a method which makes it possible to consume only certain substances and elements in minute quantities, without having to use ordinary food. It is the basis for subtle practices to purify the body and refine the mind.)

The master replied: “However hard you try, without any fruit of past generosity, propitiating the wealth deities will be difficult. Moreover, seeking wealth for this life conflicts with the sincere practice of Dharma. To practise extracting the essences of things is no longer what it used to be in the ascending kalpa,* before the essence of earth, stones, water, plants and so on had dissipated. These days it will never work. Resigning yourself to certain death is no good either. Later it could prove difficult to find another human life with all the freedoms and advantages that you have now. However, if you feel certain from the depth of your heart that you can practice without caring whether you die or not, you will never lack food and clothing.”

(*Ascending or descending can be applied to the qualities of different kalpas or refer to a smaller timescale: for instance our present times are an era of degeneration compared to the time of Shakyamuni.)

There is no example of a practitioner ever dying of hunger. The Buddha declared that even during a famine so extreme that to buy a measure of flour would cost a measure of pearls, the disciples of the Buddha would never be without food and clothing.

All the practices that Bodhisattvas undertake to accumulate merit and wisdom, or to dissolve obscurations, have but one goal: the welfare of all living creatures throughout space. Any wish to attain perfect Buddhahood just for your own sake, let alone practice aimed at accomplishing the goals of this life, has nothing whatever to do with the Great Vehicle. Whatever practice you may do, whether accumulating merit and wisdom or purifying obscurations, do it for the benefit of the whole infinity of beings, and do not mix it with any self centred desires. That way, as a secondary effect, even without your wishing it, your own interests, and comfort and happiness in this life will automatically be taken care of, just like smoke rising by itself when you blow on a fire, or barley shoots springing up as a matter of course when you sow grain. But abandon like poison any impulse to devote yourself to such things for their own sake.

The Mandala of the Universe

(A three-dimensional representation of the ancient Indian cosmos as visualized in the mandala offering. The square Mount Meru, broader at the summit than at the base, is topped by the palace of Indra and surrounded by the four continents and their subcontinents. Above it are all the different realms of the gods of form and formlessness.)